I have been remiss in not writing this sooner. . . .

I have been remiss in not writing this sooner. . . .

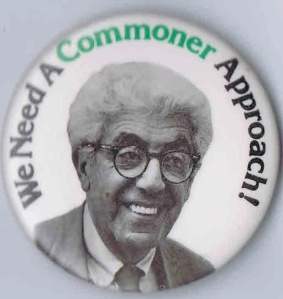

Dr. Barry Commoner, scientist, activist, educator and one of the founders of the modern environmental movement, died on September 30 at his home in Brooklyn. He was 95.

Commoner, raised in New York and educated as a biologist at Columbia and Harvard, spent a lifetime combining his grasp of science with his love of humanity, translating seemingly arcane concepts into basic principles that could inspire insight and action. He recognized early on the unexpected consequences of many post-World War II technological “miracles,” and was prescient in articulating connections between struggles for social justice and environmental health.

I met Dr. Commoner in 1980, when he brought his third-party campaign for US president to my university. Running as the candidate of the Citizens Party, which he helped found, Commoner didn’t command an auditorium (remember this was 1980, when Ronald Reagan sucked up most of the oxygen and Rep. John Anderson’s absurd “heart on the left, wallet on the right” rhetoric captured many young politicos’ third-party zeal). Instead, Commoner sat in what I remember as a smallish classroom, discussing the state of the world with an egalitarian equanimity. He knew he wasn’t going to win the election, but he had things he wanted to explain, and a level of participation he wanted to motivate.

(Years later, Commoner recalled his favorite moment of the campaign, when he was asked by a reporter, “Dr. Commoner, are you a serious candidate, or are you just running on the issues?”)

Even in that less-than-grand setting, it was still heady for a college freshman, for Commoner was not only a candidate on the national stage, he was a recognized activist and a public intellectual.

I was familiar with Barry Commoner before I got to college. As a national topic debater in high school, I had often encountered the neo-Malthusian arguments of Paul Ehrlich, author of The Population Bomb. It was common to hear that an unpleasant consequence of a supposedly beneficial plan was a drop in mortality, and so a spike in population, causing resource shortages and environmental degradation. As a debater, I had occasion to argue both pro and con, but when it was my turn to refute Ehrlich, the evidence I pulled out of my ox box was most often from Dr. Commoner.

Commoner had himself debated Professor Ehrlich in the early 1970s, noting that the high birthrates in poor communities were a form of social security, and that, in turn, those communities were poor because others were so rich. Dr. Commoner argued that rather than blame the developing world for the coming “population bomb” and the disasters it would trigger, we should focus on the wealth and resources the developed world had taken from the underprivileged:

As Commoner argued, it is rich nations that consume a disproportionate share of the world’s resources. And it was their systems of colonialism and imperialism that led to the exploitation of the Third World’s natural resources for consumption in the wealthy nations, making the poor even poorer. Without the financial resources to improve their living conditions, people in developing countries relied more heavily upon increased birthrates as a form of social security than did people in wealthier nations.

As Commoner wrote, “The poor countries have high birthrates because they are extremely poor, and they are extremely poor because other countries are extremely rich.” His solution to the population problem was to increase the standard of living of the world’s poor, which would result in a voluntary reduction of fertility, as has occurred in the rich countries.

Or as it was explained elsewhere:

Reducing population, Dr. Commoner wrote, was “equivalent to attempting to save a leaking ship by lightening the load and forcing passengers overboard.”

“One is constrained to ask if there isn’t something radically wrong with the ship.”

It was Commoner’s attention to the means of production as the crux of the problem–instead of the labor or the consumers–that gave his ideas a common sense and a compassion that the neo-Malthusians’ lacked.

And it was that sense, that compassion, and that (dare I use this word?) simplicity that always carried the day with me.

Indeed, some have mentioned that it is hard to recognize Barry Commoner’s monumental importance today because so many of the ideas that once got him labeled a radical are now just considered basic fact. The late evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould wrote in a 1990 review of Commoner’s book Making Peace with the World that it “suffers the commonest of unkind fates: to be so self-evidently true and just that we pass it by as a twice-told tale.”

Baby teeth

Of particular note here would be Dr. Commoner’s seminal activism on nuclear weapons and nuclear power. As he explained in a 1993 interview, “The Atomic Energy Commission turned me into an environmentalist.” (The US Atomic Energy Commission, a sort of hybrid precursor to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the Department of Energy, was responsible for not only America’s nuclear weapons program, but both the promotion and regulation of civilian nuclear power, as well. It was an unhealthy mix, to say the least.)

Between 1945 and 1963, the US conducted 206 tests of nuclear weapons in the atmosphere (100 in Nevada, 106 in the Pacific); the Soviet Union conducted 216 such tests. By the early 1950s, some scientists, Dr. Commoner among them, became acutely aware that fallout from those tests was sweeping across the hemisphere, eventually returning to earth in precipitation, and entering the food chain through farms and dairies.

To help make that point, Dr. Commoner (along with Drs. Louise and Eric Reiss) founded the Baby Tooth Survey. In order to demonstrate that fallout was widespread and had worked its way into the population, the project sought to track strontium-90, a radioactive isotope that occurs as a result (and only as a result) of nuclear fission. Sr-90 is structurally similar to calcium, and so, once in the body, works its way into bones and teeth. Commoner, through the auspices of Washington University (where he then taught) and the St. Louis Citizens’ Committee for Nuclear Information, collected baby teeth, initially from the area, eventually from around the globe, and analyzed them for strontium.

The program eventually collected well over a quarter-million teeth, and ultimately found that children in St. Louis in 1963 had 50 times more Sr-90 in them than children born in 1950. Armed with preliminary results from this survey and a petition signed by thousands of scientists worldwide, Dr. Commoner successfully lobbied President John F. Kennedy to negotiate and sign the Partial Test Ban Treaty, halting atmospheric nuclear tests by both the US and USSR.

The initial survey, which ended in 1970, continues to have relevance today. Some 85,000 teeth not used in the original project were turned over to researchers at the Radiation and Public Health Project (RPHP) in 2001. The RPHP study, released in 2010, found that donors from the original survey who had died of cancer before age 50 averaged over twice the Sr-90 in their samples compared with those who had lived past their 50th birthday.

Dr. Commoner also understood that many of the perils of radioactive fallout could also be associated with the radiological pollution that is part-and-parcel of nuclear power generation. The controlled fission in a nuclear reactor produces all of the elements created in the uncontrolled fission of a nuclear explosion. This point was brought home by the RPHP work, when it found strontium-90 was 30- to 50-percent higher in baby teeth collected from children that grew up near nuclear power plants.

The connection between radiological pollution and cancer will seem like a short putt to most readers here, but that is because of the pioneering work and public passion of Barry Commoner.

[Programming note: The director of the Radiation and Public Health Project, Joseph Mangano, will join me for a live chat on Saturday, October 13, at 5 PM Eastern time, to discuss his new book, Mad Science: The Nuclear Power Experiment, as part of the FDL Book Salon at Firedoglake.com.]

Everything is connected

The broad reach and broader implications of the Baby Tooth Survey are a good example of the principles that drove Barry Commoner throughout his life. The connectivity of issues and the connectedness of the world’s people made the fight against nuclear weapons and the fight for clean, renewable energy part of the same struggle. Dr. Commoner thought that if the ecology movement, the civil rights movement, the women’s equality movement and organized labor could work together, they could remake society. In later years, he lamented the economic and political divisions that prevented this cooperation from happening.

But it is perhaps best to view Commoner’s life’s work through what he called his “four laws of ecology“:

- Everything is connected to everything else.

- Everything must go somewhere.

- Nature knows best.

- There is no such thing as a free lunch.

Again, it seems so basic now, but when offered up against the technology-worshiping capitalist utopianism of the post-war era, it was actually quite controversial.

And again, with a particular mind toward nuclear power, those four laws should go without saying. But when the nuclear industry, its lobbyists, proxies and political cronies all make light of past evidence and future concerns in their effort to prop up a mythical “nuclear renaissance,” maybe a rereading of Commoner’s arguments is necessary:

In his best-selling book The Poverty of Power (1976), Commoner introduced what he called the “Three Es”—the threat to environmental survival, the shortage of energy and the problems (such as inequality and unemployment) of the economy—and explained their interconnectedness: industries that use the most energy have the most negative impact on the environment. Our dependence on nonrenewable sources of energy inevitably leads to those resources becoming scarcer, raising the cost of energy and hurting the economy.

Nuclear power is, of course, a massive consumer of energy and resources. It is a tax on the environment and the economy, and in the end only perpetuates inequality and suffering. And, as for the problem of nuclear waste, well, “everything must go somewhere.”

But back in high school, when I was but a curly-haired boy in a three-piece suit pulling four-by-six cards out of a file, I had only a vague notion of all that. What did seem clear, however, was that it wasn’t wrong to want a better life for yourself while still caring about the lives of others. What did seem clear was that suffering was not the fault of the poor, nor should it be their inescapable lot.

And clearer still, by the time I was of voting age, was that neither the policies of Jimmy Carter nor Ronald Reagan were going to get the US anywhere close to that ideal. Nor was it possible to honestly profess a love for social justice while singing the virtues of laissez-faire capitalism (à la John Anderson).

It would probably not be hard to imagine today just how depressing it was for a newly enfranchised, politically aware kid to be offered only those options on his first ballot. Thanks to Dr. Barry Commoner, back in 1980, this kid had another choice.

You must be logged in to post a comment.