[Note: On Saturday afternoon, I hosted FDL Book Salon, featuring a live Q&A with Joseph Mangano, author of Mad Science: The Nuclear Power Experiment. This is a repost of that discussion.]

[Note: On Saturday afternoon, I hosted FDL Book Salon, featuring a live Q&A with Joseph Mangano, author of Mad Science: The Nuclear Power Experiment. This is a repost of that discussion.]

In December of 1962, Consolidated Edison, New York City’s main purveyor of electricity, announced that it had submitted an official proposal to the US Atomic Energy Commission (the AEC, the precursor to today’s Nuclear Regulatory Commission) for the construction of a nuclear power plant on a site called Ravenswood. . . in Queens. . . on the East River. . . directly across from the United Nations. . . within five miles of roughly five million people.

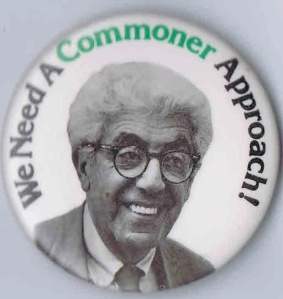

Ravenswood became the site of America’s first demonstrations against nuclear power. It inspired petitions to President John F. Kennedy and NYC Mayor Robert Wagner, and the possibility of a nuclear reactor in such a densely populated area even invited public skepticism from the pro-nuclear head of the AEC, David Lilienthal. Finally, after a year of pressure, led by the borough’s community leaders, Con Edison withdrew their application.

But within three years, reports suggested Con Ed had plans to build a nuclear plant under Central Park. After that idea was roundly criticized, the utility publicly proposed a reactor complex under Welfare Island (now known as Roosevelt Island), instead.

Despite the strong support of Laurence Rockefeller, the brother of New York State’s governor, the Welfare Island project disappeared from Con Ed’s plans by 1970. . . soon to be replaced by the idea of a nuclear “jetport”–artificial islands to be built in the ocean just south of New York City that would host a pair of commercial reactors.

Does that sound like madness? Well, from today’s perspective–with Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, and now Fukushima universally understood as synonyms for disaster–it probably does. But there was a time before those meltdowns when nuclear power still had a bit of a glow, when, despite (or because of) the devastation from the atomic bombs dropped on Japan, many believed that the atom’s awesome power could be harnessed for good; a time when dangerous and deadly mishaps at a number of the nation’s earlier reactors were easily excused or kept completely secret.

In Mad Science: The Nuclear Power Experiment, Joseph Mangano returns to that time, and then methodically pulls back the curtain on the real history of nuclear folly and failure, and the energy source that continues to masquerade as clean, safe, and “too cheap to meter.”

From Chalk River, in Canada, the world’s first reactor meltdown, through Idaho’s EBR-1, Waltz Mill, PA, Santa Susana’s failed Sodium Reactor Experiment, the Idaho National Lab explosion that killed three, Fermi-1, which almost irradiated Detroit, and, of course, Three Mile Island, Mad Science provides a chilling catalog of nuclear accidents, all of which were disasters in their own right, and all of which illustrate a troubling pattern of safety breeches followed by secrecy and lies.

Nuclear power’s precarious existence is not, of course, just a story for the history books, and Mangano also details the state of America’s 104 remaining reactors. So many of today’s plants have problems, too, but perhaps the maddest thing about the mad science of civilian atomic power is that science often plays a minor role in decisions about the technology’s future.

From its earliest days, this supposedly super-cheap energy was financially unsustainable. By the mid-1950s, private insurers had turned their back on nuclear facilities, fearing the massive payouts that would follow any accident. The nuclear industry turned to the US government, and in 1957, the Price-Anderson Act limited a plant’s liability to an artificially low but apparently insurable figure–any damage beyond that would be covered by US taxpayers. Shippingport, America’s first large-scale commercial nuclear reactor, was built entirely with government money, and that is hardly an isolated story. Even before the Three Mile Island meltdown, Wall Street had walked away from nuclear energy, meaning that no new reactors could be built without massive federal loan guarantees.

Indeed, the cost of construction, when piled on top of the cost of fueling, skilled labor, operation and upkeep, made the prospect of opening a new nuclear plant financially unpalatable. So, as Mangano explains, nuclear utilities turned to another strategy for making their vertical profitable, one familiar to any student of late Western capitalism. Rather than build, energy companies would instead buy. Since the 1990s, the nuclear sector has seen massive consolidation. Mergers and acquisitions have created nuclear mega-corporations, like Exelon, Duke, and Entergy, which run multiple reactors across many facilities in many states. And the supposed regulators of the industry, the NRC, has encouraged this behavior by rubberstamping dozens upon dozens of 20-year license extensions, turning reactors that were supposed to be nearing the end of their functional lives into valuable assets.

But the pain of nuclear power isn’t only measured in meltdowns and money. Whether firing on all cylinders (as it were) or falling apart, nuclear plants have proven to be dangerous to the populations they are supposed to serve. Joseph Mangano, an epidemiologist by trade, and director of the Radiation and Public Health Project (RPHP), has made a career out of trying to understand the immediate and long-term effects of nuclear madness, be it from fallout, leaks, or the “permissible levels” of radioactive isotopes that are regularly released from reactors as part of normal operation.

As I mentioned earlier this week, Mangano and the RPHP are the inheritors of the Baby Tooth Survey, the groundbreaking examination of strontium levels in children born before, during and after the age of atmospheric nuclear bomb tests. The discovery of high levels of Sr-90, a radioactive byproduct of uranium fission, in the baby teeth of children born in the 1950s and ’60s led directly to the Partial Test Ban Treaty in 1963.

Mangano’s work has built on the original survey, linking elevated Sr-90 levels to cancer, and examining the increases in strontium in the bodies of children that lived close to nuclear power plants. And all of this is explained in great detail in Mad Science.

The author has also applied his expertise to the fallout from the ongoing Fukushima disaster. Last December, Mangano and Janette Sherman published a peer-reviewed article in the International Journal of Health Sciences (PDF) stating that in the 14 weeks following the start of the Japanese nuclear crisis, an estimated 14,000 excess deaths in the United States could be linked to radioactive fallout from Fukushima Daiichi. (RPHP has since revised that estimate–upward–to almost 22,000 deaths (PDF).)

That last study is not specifically detailed in Mad Science, but I hope we can touch on it today–along with some of the many equally maddening “experiments” in nuclear energy production that Mangano carefully unwraps in his book.

You must be logged in to post a comment.