From here to eternity: a small plaque on the campus of the University of Chicago commemorates the site of Fermi’s first atomic pile–and the start of the world’s nuclear waste problem. (Photo: Nathan Guy via Flickr)

On December 2, 1942, a small group of physicists under the direction of Enrico Fermi gathered on an old squash court beneath Alonzo Stagg Stadium on the Campus of the University of Chicago to make and witness history. Uranium pellets and graphite blocks had been stacked around cadmium-coated rods as part of an experiment crucial to the Manhattan Project–the program tasked with building an atom bomb for the allied forces in WWII. The experiment was successful, and for 28 minutes, the scientists and dignitaries present observed the world’s first manmade, self-sustaining nuclear fission reaction. They called it an atomic pile–Chicago Pile 1 (CP-1), to be exact–but what Fermi and his team had actually done was build the world’s first nuclear reactor.

The Manhattan Project’s goal was a bomb, but soon after the end of the war, scientists, politicians, the military and private industry looked for ways to harness the power of the atom for civilian use, or, perhaps more to the point, for commercial profit. Fifteen years to the day after CP-1 achieved criticality, President Dwight Eisenhower threw a ceremonial switch to start the reactor at Shippingport, PA, which was billed as the first full-scale nuclear power plant built expressly for civilian electrical generation.

Shippingport was, in reality, little more than a submarine engine on blocks, but the nuclear industry and its acolytes will say that it was the beginning of billions of kilowatts of power, promoted (without a hint of irony) as “clean, safe, and too cheap to meter.” It was also, however, the beginning of what is now a, shall we say, weightier legacy: 72,000 tons of nuclear waste.

Atoms for peace, problems forever

News of Fermi’s initial success was communicated by physicist Arthur Compton to the head of the National Defense Research Committee, James Conant, with artistically coded flair:

Compton: The Italian navigator has landed in the New World.

Conant: How were the natives?

Compton: Very friendly.

But soon after that initial success, CP-1 was disassembled and reassembled a short drive away, in Red Gate Woods. The optimism of the physicists notwithstanding, it was thought best to continue the experiments with better radiation shielding–and slightly removed from the center of a heavily populated campus. The move was perhaps the first necessitated by the uneasy relationship between fissile material and the health and safety of those around it, but if it was understood as a broader cautionary tale, no one let that get in the way of “progress.”

By the time the Shippingport reactor went critical, North America already had a nuclear waste problem. The detritus from manufacturing atomic weapons was poisoning surrounding communities at several sites around the continent (not that most civilians knew it at the time). Meltdowns at Chalk River in Canada and the Experimental Breeder Reactor in Idaho had required fevered cleanups, the former of which included the help of a young Navy officer named Jimmy Carter. And the dangers of errant radioisotopes were increasing with the acceleration of above-ground atomic weapons testing. But as President Eisenhower extolled “Atoms for Peace,” and the US Atomic Energy Commission promoted civilian nuclear power at home and abroad, a plan to deal with the “spent fuel” (as used nuclear fuel rods are termed) and other highly radioactive leftovers was not part of the program (beyond, of course, extracting some of the plutonium produced by the fission reaction for bomb production, and the promise that the waste generated by US-built reactors overseas could at some point be marked “return to sender” and repatriated to the United States for disposal).

Attempts at what was called “reprocessing”–the re-refining of used uranium into new reactor fuel–quickly proved expensive, inefficient and dangerous, and created as much radioactive waste as it hoped to reuse. It also provided an obvious avenue for nuclear weapons proliferation because of the resulting production of plutonium. The threat of proliferation (made flesh by India’s test of an atomic bomb in 1976) led President Jimmy Carter to cancel the US reprocessing program in 1977. Attempts by the Department of Energy to push mixed-oxide (MOX) fuel fabrication (combining uranium and plutonium) over the last dozen years has not produced any results, either, despite over $5 billion in government investments.

In fact, there was no official federal policy for the management of used but still highly radioactive nuclear fuel until passage of The Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982. And while that law acknowledged the problem of thousands of tons of spent fuel accumulating at US nuclear plants, it didn’t exactly solve it. Instead, the NWPA started a generation of political horse trading, with goals and standards defined more by market exigencies than by science, that leaves America today with what amounts to over five-dozen nominally temporary repositories for high-level radioactive waste–and no defined plan to change that situation anytime soon.

When you assume…

When a US Court of Appeals ruled in June that the Nuclear Regulatory Commission acted improperly when it failed to consider all the risks of storing spent radioactive fuel onsite at the nation’s nuclear power facilities, it made specific reference to the lack of any real answers to the generations-old question of waste storage:

[The Nuclear Regulatory Commission] apparently has no long-term plan other than hoping for a geologic repository. . . . If the government continues to fail in its quest to establish one, then SNF (spent nuclear fuel) will seemingly be stored on site at nuclear plants on a permanent basis. The Commission can and must assess the potential environmental effects of such a failure.

The court concluded the current situation–where spent fuel is stored across the country in what were supposed to be temporary configurations–“poses a dangerous long-term health and environmental risk.”

The decision also harshly criticized regulators for evaluating plant relicensing with the assumption that spent nuclear fuel would be moved to a central long-term waste repository.

A mountain of risks

The Nuclear Waste Policy Act set in motion an elaborate process that was supposed to give the US a number of possible waste sites, but, in the end, the only option seriously explored was the Yucca Mountain site in Nevada. After years of preliminary construction and tens of millions of dollars spent, Yucca was determined to be a bad choice for the waste:

[Yucca Mountain’s] volcanic formation is more porous and less isolated than originally believed–there is evidence that water can seep in, there are seismic concerns, worries about the possibility of new volcanic activity, and a disturbing proximity to underground aquifers. In addition, Yucca mountain has deep spiritual significance for the Shoshone and Paiute peoples.

Every major Nevada politician on both sides of the aisle has opposed the Yucca repository since its inception. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid has worked most of his political life to block the facility. And with the previous NRC head, Gregory Jaczko, (and now his replacement, Allison Macfarlane, as well) recommending against it, the Obama administration’s Department of Energy moved to end the project.

Even if it were an active option, Yucca Mountain would still be many years and maybe as much as $100 million away from completion. And yet, the nuclear industry (through recipients of its largesse in Congress) has challenged the administration to spend any remaining money in a desperate attempt to keep alive the fantasy of a solution to their waste crisis.

Such fevered dreams, however, do not qualify as an actual plan, according to the courts.

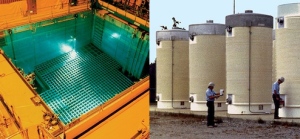

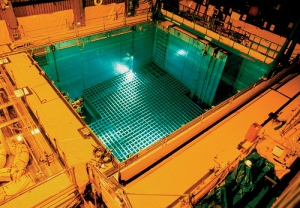

The judges also chastised the NRC for its generic assessment of spent fuel pools, currently packed well beyond their projected capacity at nuclear plants across the United States. Rather than examine each facility and the potential risks specific to its particular storage situation, the NRC had only evaluated the safety risks of onsite storage by looking at a composite of past events. The court ruled that the NRC must appraise each plant individually and account for potential future dangers. Those dangers include leaks, loss of coolant, and failures in the cooling systems, any of which might result in contamination of surrounding areas, overheating and melting of stored rods, and the potential of burning radioactive fuel–risks heightened by the large amounts of fuel now densely packed in the storage pools and underscored by the ongoing disaster at Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi plant.

Indeed, plants were not designed nor built to house nuclear waste long-term. The design life of most reactors in the US was originally 40 years. Discussions of the spent fuel pools usually gave them a 60-year lifespan. That limit seemed to double almost magically as nuclear operators fought to postpone the expense of moving cooler fuel to dry casks and of the final decommissioning of retired reactors.

Everyone out of the pool

As disasters as far afield as the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and last October’s Hurricane Sandy have demonstrated, the storage of spent nuclear fuel in pools requires steady supplies of power and cool water. Any problem that prevents the active circulation of liquid through the spent fuel pools–be it a loss of electricity, the failure of a back-up pump, the clogging of a valve or a leak in the system–means the temperature in the pools will start to rise. If the cooling circuit is out long enough, the water in the pools will start to boil. If the water level dips (due to boiling or a leak) enough to expose hot fuel rods to the air, the metal cladding on the rods will start to burn, in turn heating the fuel even more, resulting in plumes of smoke carrying radioactive isotopes into the atmosphere.

And because these spent fuel pools are so full–containing as much as five times more fuel than they were originally designed to hold, and at densities that come close to those in reactor cores–they both heat stagnant water more quickly and reach volatile temperatures faster when exposed to air.

After spent uranium has been in a pool for at least five years (considerably longer than most fuel is productive as an energy source inside the reactor), fuel rods are deemed cool enough to be moved to dry casks. Dry casks are sealed steel cylinders filled with spent fuel and inert gas, which are themselves encased in another layer of steel and concrete. These massive fuel “coffins” are then placed outside, spaced on concrete pads, so that air can circulate and continue to disperse heat.

While the long-term safety of dry casks is still in question, the fact that they require no active cooling system gives them an advantage, in the eyes of many experts, over pool storage. As if to highlight that difference, spent fuel pools at Fukushima Daiichi have posed some of the greatest challenges since the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami, whereas, to date, no quake or flood-related problems have been reported with any of Japan’s dry casks. The disparity was so obvious, that the NRC’s own staff review actually added a proposal to the post-Fukushima taskforce report, recommending that US plants take more fuel out of spent fuel pools and move it to dry casks. (A year-and-a-half later, however, there is still no regulation–or even a draft–requiring such a move.)

But current dry cask storage poses its own set of problems. Moving fuel rods from pools to casks is slow and costly–about $1.5 million per cask, or roughly $7 billion to move all of the nation’s spent fuel (a process, it is estimated, that would take no less than five to ten years). That is expensive enough to have many nuclear plant operators lobbying overtime to avoid doing it.

Further, though not as seemingly vulnerable as fuel pools, dry casks are not impervious to natural disaster. In 2011, a moderate earthquake centered about 20 miles from the North Anna, Virginia, nuclear plant caused most of its vertical dry casks–each weighing 115 tons–to shift, some by more than four inches. The facility’s horizontal casks didn’t move, but some showed what was termed “cosmetic damage.”

Dry casks at Michigan’s Palisades plant sit on a pad atop a sand dune just 100 yards from Lake Michigan. An earthquake there could plunge the casks into the water. And the casks at Palisades are so poorly designed and maintained, submersion could result in water contacting the fuel, contaminating the lake and possibly triggering a nuclear chain reaction.

And though each cask contains far less fissile material than one spent fuel pool, casks are still considered possible targets for terrorism. A TOW anti-tank missile would breach even the best dry cask (PDF), and with 25 percent of the nation’s spent fuel now stored in hundreds of casks across the country, all above ground, it provides a rich target environment.

Confidence game

Two months after the Appeals Court found fault with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s imaginary waste mitigation scenario, the NRC announced it would suspend the issuing of new reactor operating licenses, license renewals and construction licenses until the agency could craft a new plan for dealing with the nation’s growing spent nuclear fuel crisis. In drafting its new nuclear “Waste Confidence Decision” (NWCD)–the methodology used to assess the hazards of nuclear waste storage–the Commission said it would evaluate all possible options for resolving the issue.

At first, the NRC said this could include both generic and site-specific actions (remember, the court criticized the NRC’s generic appraisals of pool safety), but as the prescribed process now progresses, it appears any new rule will be designed to give the agency, and so, the industry, as much wiggle room as possible. At a public hearing in November, and later at a pair of web conferences in early December, the regulator’s Waste Confidence Directorate (yes, that’s what it is called) outlined three scenarios (PDF) for any future rulemaking:

- Storage until a repository becomes available at the middle of the century

- Storage until a repository becomes available at the end of the century

- Continued storage in the event a repository is not available

And while, given the current state of affairs, the first option seems optimistic, the fact that their best scenario now projects a repository to be ready by about 2050 is a story in itself.

When the Nuclear Waste Policy Act was signed into law by President Reagan early in 1983, it was expected the process it set in motion would present at least one (and preferably another) long-term repository by the late 1990s. But by the time the “Screw Nevada Bill” (as it is affectionately known in the Silver State) locked in Yucca Mountain as the only option for permanent nuclear waste storage, the projected opening was pushed back to 2007.

But Yucca encountered problems from its earliest days, so a mid-’90s revision of the timeline postponed the official start, this time to 2010. By 2006, the Department of Energy was pegging Yucca’s opening at 2017. And, when the NWPA was again revised in 2010–after Yucca was deemed a non-option–it conveniently avoided setting a date for the opening of a national long-term waste repository altogether.

It was that 2010 revision that was thrown out by the courts in June.

“Interim storage” and “likely reactors”

So, the waste panel now has three scenarios–but what are the underlying assumptions for those scenarios? Not, obviously, any particular site for a centralized, permanent home for the nation’s nuclear garbage–no new site has been chosen, and it can’t even be said there is an active process at work that will choose one.

There are the recommendations of a Blue Ribbon Commission (BRC) convened by the president after Yucca Mountain was off the table. Most notable there, was a recommendation for interim waste storage, consolidated at a handful of locations across the country. But consolidated intermediate waste storage has its own difficulties, not the least of which is that no sites have yet been chosen for any such endeavor. (In fact, plans for the Skull Valley repository, thought to be the interim facility closest to approval, were abandoned by its sponsors just days before Christmas.)

Just-retired New Mexico Senator Jeff Bingaman (D), the last chair of the Energy and Natural Resources Committee, tried to turn the BRC recommendations into law. When he introduced his bill in August, however, he had to do so without any cosponsors. Hearings on the Nuclear Waste Administration Act of 2012 were held in September, but the gavel came down on the 112th Congress without any further action.

In spite of the underdeveloped state of intermediate storage, however, when the waste confidence panel was questioned on the possibility, interim waste repositories seemed to emerge, almost on the fly, as an integral part of any revised waste policy rule.

“Will any of your scenarios include interim centralized above-ground storage?” we asked during the last public session. Paul Michalak, who heads the Environmental Impact Statement branch of the Waste Confidence Directorate, first said temporary sites would be considered in the second and third options. Then, after a short pause, Mr. Michalak added (PDF p40), “First one, too. All right. Right. That’s right. So we’re considering an interim consolidated storage facility [in] all three scenarios.”

The lack of certainty on any site or sites is, however, not the only fuzzy part of the picture. As mentioned earlier, the amount of high-level radioactive waste currently on hand in the US and in need of a final resting place is upwards of 70,000 tons–already at the amount that was set as the initial limit for the Yucca Mountain repository. Given that there are still over 100 domestic commercial nuclear reactors more or less in operation, producing something like an additional 2,000 tons of spent fuel every year, what happens to the Waste Confidence Directorate’s scenarios as the years and waste pile up? How much waste were regulators projecting they would have to deal with–how much spent fuel would a waste confidence decision assume the system could confidently handle?

There was initial confusion on what amount of waste–and at what point in time–was informing the process. Pressed for clarification on the last day of hearings, NRC officials finally posited that it was assumed there would be 150,000 metric tons of spent fuel–all deriving from the commercial reactor fleet–by 2050. By the end of the century, the NRC expects to face a mountain of waste weighing 270,000 metric tons (PDF pp38-41) (though this figure was perplexingly termed both a “conservative number” and an “overestimate”).

How did the panel arrive at these numbers? Were they assuming all 104 (soon to be 103–Wisconsin’s Kewaunee Power Station will shut down by mid-2013 for reasons its owner, Dominion Resources, says are based “purely on economics”) commercial reactors nominally in operation would continue to function for that entire time frame–even though many are nearing the end of their design life and none are licensed to continue operation beyond the 2030s? Were they counting reactors like those at San Onofre, which have been offline for almost a year, and are not expected to restart anytime soon? Or the troubled reactors at Ft. Calhoun in Nebraska and Florida’s Crystal River? Neither facility has been functional in recent years, and both have many hurdles to overcome if they are ever to produce power again. Were they factoring in the projected AP1000 reactors in the early stages of construction in Georgia, or the ones slated for South Carolina? Did the NRC expect more or fewer reactors generating waste over the course of the next 88 years?

The response: waste estimates include all existing facilities, plus “likely reactors”–but the NRC cannot say exactly how many reactors that is (PDF p41).

Jamming it through

Answers like those from the Waste Confidence Directorate do not inspire (pardon the expression) confidence for a country looking at a mountain of eternally toxic waste. Just what would the waste confidence decision (and the environmental impact survey that should result from it) actually cover? What would it mandate, and what would change as a result?

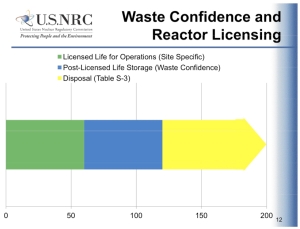

How long is it? Does this NRC chart provide a justification for the narrow scope of the waste confidence process? (US Nuclear Regulatory PDF, p12)

In past relicensing hearings–where the public could comment on proposed license extensions on plants already reaching the end of their 40-year design life–objections based on the mounting waste problem and already packed spent fuel pools were waived off by the NRC, which referenced the waste confidence decision as the basis of its rationale. Yet, when discussing the parameters of the process for the latest, court-ordered revision to the NWCD, Dr. Keith McConnell, Director of the Waste Confidence Directorate, asserted that waste confidence was not connected to the site-specific licensed life of operations (PDF p42), but only to a period defined as “Post-Licensed Life Storage” (which appears, if a chart in the directorate’s presentation (PDF p12) is to be taken literally, to extend from 60 years after the initial creation of waste, to 120 years–at which point a phase labeled “Disposal” begins). Issues of spent fuel pool and dry cask safety are the concerns of a specific plant’s relicensing process, said regulators in the latest hearings.

“It’s like dealing with the Mad Hatter,” commented Kevin Kamps, a radioactive waste specialist for industry watchdog Beyond Nuclear. “Jam yesterday, jam tomorrow, but never jam today.”

The edict originated with the White Queen in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass, but it is all too appropriate–and no less maddening–when trying to motivate meaningful change at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. The NRC has used the nuclear waste confidence decision in licensing inquiries, but in these latest scoping hearings, we are told the NWCD does not apply to on-site waste storage. The Appeals Court criticized the lack of site-specificity in the waste storage rules, but the directorate says they are now only working on a generic guideline. The court disapproved of the NRC’s continued relicensing of nuclear facilities based on the assumption of a long-term geologic repository that in reality did not exist–and the NRC said it was suspending licensing pending a new rule–but now regulators say they don’t anticipate the denial or even the delay of any reactor license application while they await the new waste confidence decision (PDF pp49-50).

In fact, the NRC has continued the review process on pending applications, even though there is now no working NWCD–something deemed essential by the courts–against which to evaluate new licenses.

The period for public comment on the scope of the waste confidence decision ended January 2, and no more scoping hearings are planned. There will be other periods for civic involvement–during the environmental impact survey and rulemaking phases–but, with each step, the areas open to input diminish. And the current schedule has the entire process greatly accelerated over previous revisions.

On January 3, a coalition of 24 grassroots environmental groups filed documents with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (PDF) protesting “the ‘hurry up’ two-year timeframe” for this assessment, noting the time allotted for environmental review falls far short of the 2019 estimate set by the NRC’s own technical staff. The coalition observed that two years was also not enough time to integrate post-Fukushima recommendations, and that the NRC was narrowing the scope of the decision–ignoring specific instructions from the Appeals Court–in order to accelerate the drafting of a new waste storage rule.

Speed might seem a valuable asset if the NRC were shepherding a Manhattan Project-style push for a solution to the ever-growing waste problem–the one that began with the original Manhattan Project–but that is not what is at work here. Instead, the NRC, under court order, is trying to set the rules for determining the risk of all that high-level radioactive waste if there is no new, feasible solution. The NRC is looking for a way to permit the continued operation of the US nuclear fleet–and so the continued manufacture of nuclear waste–without an answer to the bigger, pressing question.

A plan called HOSS

While there is much to debate about what a true permanent solution to the nuclear waste problem might look like, there is little question that the status quo is unacceptable. Spent fuel pools were never intended to be used as they are now used–re-racked and densely packed with over a generation of fuel assemblies. Both the short- and long-term safety and security of the pools has now been questioned by the courts and laid bare by reality. Pools at numerous US facilities have leaked radioactive waste (PDF) into rivers, groundwater and soil. Sudden “drain downs” have come perilously close to triggering major accidents in plants shockingly close to major population centers. Recent hurricanes have knocked out power to cooling systems and flooded backup generators, and last fall’s superstorm came within inches of overwhelming the coolant intake structure at Oyster Creek in New Jersey.

The crisis at Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi facility was so dangerous and remains dangerous to this day in part because of the large amounts of spent fuel stored in pools next to the reactors but outside of containment–a design identical to 35 US nuclear reactors. A number of these GE Mark 1 Boiling Water Reactors–such as Oyster Creek and Vermont Yankee–have more spent fuel packed into their individual pools than all the waste in Fukushima Daiichi Units 1, 2, 3, and 4 combined.

Dry casks, the obvious next “less-bad” option for high-level radioactive waste, were also not supposed to be a permanent panacea. The design requirements and manufacturing regulations of casks–especially the earliest generations–do not guarantee their reliability anywhere near the 100 to 300 years now being casually tossed around by NRC officials. Some of the nation’s older dry casks (which in this case means 15 to 25 years) have already shown seal failures and structural wear (PDF). Yet, the government does not require direct monitoring of casks for excessive heat or radioactive leaks–only periodic “walkthroughs.”

Add in the reluctance of plant operators to spend money on dry cask transfer and the lack of any workable plan to quickly remove radioactive fuel from failed casks, and dry cask storage also appears to fail to attain any court-ordered level of confidence.

Interim plans, such as regional consolidated above-ground storage, remain just that–plans. There are no sites selected and no designs for such a facility up for public scrutiny. What is readily apparent, though, is that the frequent transport of nuclear waste increases the risk of nuclear accidents. There does not, as of now, exist a transfer container that is wholly leak proof, accident proof, and impervious to terrorist attack. Moving high-level radioactive waste across the nation’s highways, rail lines and waterways has raised fears of “Mobile Chernobyls” and “Floating Fukushimas.”

More troubling still, if past (and present) is prologue, is the tendency of options designed as “interim” to morph into a default “permanent.” Can the nation afford to kick the can once more, spending tens (if not hundreds) of millions of dollars on a “solution” that will only add a collection of new challenges to the existing roster of problems? What will the interim facilities become beyond the next problem, the next site for costly mountains of poorly stored, dangerous waste?

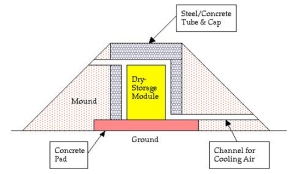

Hardened: The more robust HOSS option as proposed in 2003. (From “Robust Storage of Spent Nuclear Fuel: A Neglected Issue of Homeland Security” courtesy of the Nuclear Information and Resource Service)

If there is an interim option favored by many nuclear experts, engineers and environmentalists (PDF), it is something called HOSS–Hardened On-Site Storage (PDF). HOSS is a version of dry cask storage that is designed and manufactured to last longer, is better protected against leaks and better shielded from potential attacks. Proposals (PDF) involve steel, concrete and earthen barriers incorporating proper ventilation and direct monitoring for heat and radiation.

But not all reactor sites are good candidates for HOSS. Some are too close to rivers that regularly flood, some are vulnerable to the rising seas and increasingly severe storms brought on by climate change, and others are close to active geologic fault zones. For facilities where hardened on-site storage would be an option, nuclear operators will no doubt fight the requirements because of the increased costs above and beyond the price of standard dry cask storage, which most plant owners already try to avoid or delay.

The first rule of holes

Mixed messages: A simple stone marker in Red Gate Woods, just outside Chicago, tries to both warn and reassure visitors to this public park. (Photo: Kevin Kamps, Beyond Nuclear. Used by permission.)

In a wooded park just outside Chicago sits a dirt mound, near a bike path, that contains parts of the still-highly radioactive remains of CP-1, the world’s first atomic pile. Seven decades after that nuclear fuel was first buried, many health experts would not recommend that spot (PDF) for a long, languorous picnic, nor would they recommend drinking from nearby water fountains. To look at it in terms Arthur Compton might favor, when it comes to the products of nuclear chain reactions, the natives are restless. . . and will remain so for millennia to come.

One can perhaps forgive those working in the pressure cooker of the Manhattan Project and in the middle of a world war for ignoring the forest for the trees–for not considering waste disposal while pursuing a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction. Perhaps. But, as the burial mound in Red Gate Woods reminds us, ignoring a problem does not make it go away.

And if that small pile, or the mountains of spent fuel precariously stored around the nation are not enough of a prompt, the roughly $960 million that the federal government has had to pay private nuclear operators should be. For every year that the Department of Energy does not provide a permanent waste repository–or at least some option that takes the burden of storing spent nuclear fuel off the hands (and off the books) of power companies–the government is obligated to reimburse the industry for the costs of onsite waste storage. By 2020, it is estimated that $11 billion in public money will have been transferred into the pockets of private nuclear companies. By law, these payments cannot be drawn from the ratepayer-fed fund that is earmarked for a permanent geologic repository, and so, these liabilities must be paid out of the federal budget. Legal fees for defending the DoE against these claims will add another 20 to 30 percent to settlement costs.

The Federal Appeals Court, too, has sent a clear message that the buck needs to stop somewhere at some point–and that such a time and place should be both explicit and realistic. The nuclear waste confidence scoping process, however, is already giving the impression that the NRC’s next move will be generic and improbable.

The late, great Texas journalist Molly Ivins once remarked, “The first rule of holes” is “when you’re in one, stop digging.” For high-level radioactive waste, that hole is now a mountain, over 70 years in the making and over 70,000 tons high. If the history of the atomic age is not evidence enough, the implications of the waste confidence decision process put the current crisis in stark relief. There is, right now, no good option for dealing with the nuclear detritus currently on hand, and there is not even a plan to develop a good option in the near future. Without a way to safely store the mountain of waste already created, under what rationale can a responsible government permit the manufacture of so much more?

The federal government spends billions to perpetuate and protect the nuclear industry–and plans to spend billions more to expand the number of commercial reactors. Dozens of facilities already are past, or are fast approaching, the end of their design lives, but the Nuclear Regulatory Commission has yet to reject any request for an operating license extension–and it is poised to approve many more, nuclear waste confidence decision not withstanding. Plant operators continue to balk at any additional regulations that would require better waste management.

The lesson of the first 70 years of fission is that we cannot endure more of the same. The government–from the DoE to the NRC–should reorient its priorities from creating more nuclear waste to safely and securely containing what is now here. Money slated for subsidizing current reactors and building new ones would be better spent on shuttering aging plants, designing better storage options for their waste, modernizing the electrical grid, and developing sustainable energy alternatives. (And reducing demand through conservation programs should always be part of the conversation.)

Enrico Fermi might not have foreseen (or cared about) the mountain of waste that began with his first atomic pile, but current scientists, regulators and elected officials have the benefit of hindsight. If the first rule of holes says stop digging, then the dictum here should be that when you’re trying to summit a mountain, you don’t keep shoveling more garbage on top.

A version of this story previously appeared on Truthout; no version may be reprinted without permission.

You must be logged in to post a comment.