At roughly 5:30 in the morning on July 16, 1945, an implosion-design plutonium device, codenamed “the gadget,” exploded over the Jornada del Muerto desert in south-central New Mexico with a force equivalent to about 20,000 tons of TNT. It was the world’s first test of an atomic bomb, and as witnesses at base camp some ten miles away would soon relay to US President Harry Truman, the results were “satisfactory” and exceeded expectations. Within weeks, the United States would use a uranium bomb of a different design on the Japanese city of Hiroshima, and three days after that, a plutonium device similar to the gadget was dropped on Nagasaki, about 200 miles to the southwest.

At roughly 5:30 in the morning on July 16, 1945, an implosion-design plutonium device, codenamed “the gadget,” exploded over the Jornada del Muerto desert in south-central New Mexico with a force equivalent to about 20,000 tons of TNT. It was the world’s first test of an atomic bomb, and as witnesses at base camp some ten miles away would soon relay to US President Harry Truman, the results were “satisfactory” and exceeded expectations. Within weeks, the United States would use a uranium bomb of a different design on the Japanese city of Hiroshima, and three days after that, a plutonium device similar to the gadget was dropped on Nagasaki, about 200 miles to the southwest.

Though Hiroshima and Nagasaki are the only instances where atomic weapons were used against a wartime enemy, between 1945 and 1963, the world experienced hundreds upon hundreds of nuclear weapons tests, the great majority of which were above ground or in the sea–in other words, in the atmosphere. The US tested atom and hydrogen bombs in Nevada, at the Nevada Test Site, and in the Pacific Ocean, on and around the Marshall Islands, in an area known as the Pacific Proving Grounds. After the Soviet Union developed its own atomic weapon in 1949, it carried out hundreds of similar explosions, primarily in Kazakhstan, and the UK performed more than 20 of its own atmospheric nuclear tests, mostly in Australia and the South Pacific, between 1952 and 1958.

Though military authorities and officials with the US Atomic Energy Commission initially downplayed the dispersal and dangers of fallout from these atmospheric tests, by the early 1950s, scientists in nuclear and non-nuclear countries alike began to raise concerns. Fallout from atmospheric tests was not contained simply to the blast radius or a region near the explosion, instead the products of fission and un-fissioned nuclear residue were essentially vaporized by the heat and carried up into the stratosphere, sweeping across the globe, and eventually returning to earth in precipitation. A host of radioactive isotopes contaminated land and surface water, entering the food chain through farms and dairies.

The tale of the teeth

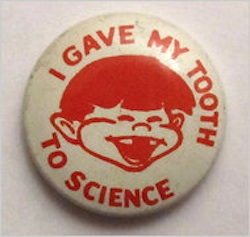

In order to demonstrate that fallout was widespread and had worked its way into the population, a group of researchers, headed by Dr. Barry Commoner and Drs. Louise and Eric Reiss, founded the Baby Tooth Survey under the auspices of Washington University (where Commoner then taught) and the St. Louis Citizens’ Committee for Nuclear Information. The tooth survey sought to track strontium-90 (Sr-90), a radioactive isotope of the alkaline earth metal strontium, which occurs as a result–and only as a result–of nuclear fission. Sr-90 is structurally similar to calcium, and so, once in the body, works its way into bones and teeth.

While harvesting human bones was impractical, researchers realized that baby teeth should be readily available. Most strontium in baby teeth would transfer from mother to fetus during pregnancy, and so birth records would provide accurate data about where and when those teeth were formed. The tooth survey collected baby teeth, initially from the St. Louis area, eventually from around the globe, and analyzed them for strontium.

By the early ’60s, the program had collected well over a quarter-million teeth, and ultimately found that children in St. Louis in 1963 had 50 times more Sr-90 in them than children born in 1950. Armed with preliminary results from this survey and a petition signed by thousands of scientists worldwide, Dr. Commoner successfully lobbied President John F. Kennedy to negotiate and sign the Partial Test Ban Treaty, halting atmospheric nuclear tests by the US, UK and USSR. By the end of the decade, strontium-90 levels in newly collected baby teeth were substantially lower than the ’63 samples.

The initial survey, which ended in 1970, continues to have relevance today. Some 85,000 teeth not used in the original project were turned over to researchers at the Radiation and Public Health Project (RPHP) in 2001. The RPHP study, released in 2010, found that donors from the Baby Tooth Survey who had died of cancer before age 50 averaged over twice the Sr-90 in their samples compared with those who had lived past their 50th birthday.

But the perils of strontium-90–or, indeed, a host of radioactive isotopes that are strontium’s travel companions–did not cease with the ban on atmospheric nuclear tests. Many of the hazards of fallout could also be associated with the radiological pollution that is part-and-parcel of nuclear power generation. The controlled fission in a nuclear reactor produces all of the elements created in the uncontrolled fission of a nuclear explosion. This point was brought home by the RPHP work, when it found strontium-90 was 30- to 50-percent higher in baby teeth collected from children born in “nuclear counties,” (PDF) the roughly 40 percent of US counties situated within 100 miles of a nuclear power plant or weapons lab.

Similar baby teeth research has been conducted over the last 30 years in Denmark, Japan and Germany, with measurably similar results. While Sr-90 levels continued to decrease in babies born through the mid 1970s, as the use of nuclear power starts to spread worldwide, that trend flattens. Of particular note, a study conducted by the German section of the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (winner of the 1985 Nobel Peace Prize) found ten-times more strontium-90 in the teeth of children born after the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster when compared with samples from 1983.

While radioactive strontium itself can be linked to several diseases, including leukemia and bone cancers, Sr-90, as mentioned above, is but one of the most measurable of many dangerous isotopes released into the environment by the normal, everyday operation of nuclear reactors, even without the catastrophic discharges that come with accidents and meltdowns. Tritium, along with radioactive variants of iodine, cesium and xenon (to name just a few) can often be detected in elevated levels in areas around nuclear facilities.

Epidemiological studies have shown higher risks of breast and prostate cancers for those living in US nuclear counties. But while the Environmental Protection Agency collects sporadic data on the presence of radioactive isotopes such as Sr-90, the exact locations of the sampling sites are not part of the data made available to the general public. Further, while “unusual” venting of radioactive vapor or the dumping of contaminated water from a nuclear plant has to be reported to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (and even then, it is the event that is reported, not the exact composition of the discharge), the radio-isotopes that are introduced into the environment by the typical operation of a reactor meet with far less scrutiny. In the absence of better EPA data and more stringent NRC oversight, studies like the Baby Tooth Survey and its contemporary brethren are central to the public understanding of the dangers posed by the nuclear power industry.

June and Sr-90: busting out all over

As if to underscore the point, strontium-90 served as the marker for troubling developments on both sides of the Pacific just this June.

In Japan, TEPCO–still the official operator of Fukushima Daiichi–revealed it had found Sr-90 in groundwater surrounding the crippled nuclear plant at “very high” levels. Between December 2012 and May 2013, levels of strontium-90 increased over 100-fold, to 1,000 becquerels per liter–33 times the Japanese limit for the radioactive isotope.

The samples were taken less than 100 feet from the coast. From that point, reports say, the water usually flows out to the Pacific Ocean.

Beyond the concerns raised by the affects of the strontium-90 (and the dangerously high amounts of tritium detected along with it) when the radioactive contamination enters the food chain, the rising levels of Sr-90 likely indicate other serious problems at Fukushima. Most obviously, there is now little doubt that TEPCO has failed to contain contaminated water leaking from the damaged reactor buildings–contrary to the narrative preferred by company officials.

But skyrocketing levels of strontium-90 could also suggest that the isotope is still being produced–that nuclear fission is still occurring in one or more of the damaged reactor cores. Or even, perhaps, outside the reactors, as the corium (the term for the molten, lava-like nuclear fuel after a meltdown) in as many as three units is believed to have melted through the steel reactor containment and possibly eroded the concrete floor, as well.

An ocean away, in Washington state, radiological waste, some of which dates back to the manufacture of those first atom bombs, sits in aging storage tanks at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation–and some of those tanks are leaking.

In truth, tanks at Hanford, considered by many the United States’ most contaminated nuclear site, have been leaking for some time. But the high-level radioactive waste in some of the old, single-wall tanks had been transferred to newer, double-walled storage, which was supposed to provide better containment. On June 20, however, the US Department of Energy reported that workers at Hanford detected radioactive contamination–specifically Sr-90–outside one of the double-walled tanks, possibly suggesting a breach. The predominant radionuclides in the 850,000-gallon tank are reported to be strontium-90 and cesium-137.

The tank, along with hundreds of others, sits about five miles from the Columbia River, water source for much of the region. Once contamination leaks from the tanks, it mixes with ground water, and, in time, should make its way to the river. “I view this as a crisis,” said Tom Carpenter, executive director of the watchdog group Hanford Challenge, “These tanks are not supposed to fail for 50 years.”

Destroyer of worlds

In a 1965 interview, J. Robert Oppenheimer, the Manhattan Project’s science director who was in charge of the Los Alamos facility that developed the first atomic bombs, looked back twenty years to that July New Mexico morning:

We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried. Most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad-Gita; Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he should do his duty and, to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.

“We knew the world would not be the same.” Oppenheimer was most likely speaking figuratively, but, as it turns out, he also reported a literal truth. Before July 16, 1945, there was no strontium-90 or cesium-137 in the atmosphere–it simply did not exist in nature. But ever since that first atomic explosion, these anthropogenic radioactive isotopes have been part of earth’s every turn.

Strontium-90–like cesium-137 and a catalog of other hazardous byproducts of nuclear fission–takes a long time to decay. The detritus of past detonations and other nuclear disasters will be quite literally with us–in our water and soil, in our tissue and bone–for generations. These radioactive isotopes have already been linked to significant suffering, disease and death. Their danger was acknowledged by the United States when JFK signed the 1963 Test Ban Treaty. Now would be a good time to acknowledge the perspicacity of that president, phase out today’s largest contributors of atmospheric Sr-90, nuclear reactors, and let the sun set on this toxic metal’s life.

A version of this story previously appeared on Truthout; no version may be reprinted without permission.

You must be logged in to post a comment.