Tag Archives: New York

LIPA’s Nuclear Legacy Leaves Sandy’s Survivors in the Dark

Head of Long Island Power Authority Steps Aside as Governor Convenes Special Commission, But Problems Have Deep Roots

The decommissioned Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant still occupies a 58-acre site on Long Island Sound. (photo: Paul Searing via Wikipedia)

As the sun set on Veterans Day, 2012, tens of thousands of homes on New York’s Long Island prepared to spend another night in darkness. The lack of light was not part of any particular memorial or observance; instead, it was the noisome and needless culmination of decades of mismanagement and malfeasance by a power company still struggling to pay for a now-moldering nuclear plant that never provided a single usable kilowatt to the region’s utility customers.

The enterprise in charge of all that darkness bears little resemblance to the sorts of power companies that provide electricity to most Americans–it is not a private energy conglomerate, nor is it really a state- or municipality-owned public utility–but the pain and frustration felt by Long Island residents should be familiar to many. And the tale of how an agency mandated by law to provide “a safer, more efficient, reliable and economical supply of electric energy” failed to deliver any of that is at its very least cautionary, and can likely serve as an object lesson for the entire country.

Almost immediately, the United States will be faced with tough choices about how to create and deliver electrical power. Those choices are defined not just by demand but by a warming climate and an infrastructure already threatened by the changes that climate brings. When one choice, made by a private concern nearly 50 years ago, means weeks of power outages and billions of dollars in repair costs today, it suggests new decisions about America’s energy strategy should be handled with care.

A stormy history

Two weeks after Hurricane-cum-Superstorm Sandy battered the eastern coast of the United States, upwards of 76,000 customers of the Long Island Power Authority (LIPA) were still without power. That number is down markedly from the one million LIPA customers (91 percent of LIPA’s total customer base) that lost power as Sandy’s fierce winds, heavy rains and massive storm surge came up the Atlantic Coast on Monday, October 29, and down, too, from the over 300,000 still without service on election day, but at each step of the process, consumers and outside observers alike agreed it was too many waiting too long.

And paying too much. LIPA customers suffer some of the highest utility rates in the country, and yet, the power outages that came with last month’s storm–and a subsequent snowstorm nine days later–while disgraceful, were far from unexpected. The Long Island Power Authority and its corporate predecessor, the Long Island Lighting Company (LILCO), have a long track record of service failures and glacial disaster response times dating back to Hurricane Gloria, which hit the region in the autumn of 1985.

After Gloria, when many Long Island homes lost power for two weeks, and again after widespread outages resulted from 2011’s Hurricane Irene, the companies responsible for providing electricity to the residents of most of Nassau and Suffolk Counties, along with parts of the Borough of Queens in New York City, were told to make infrastructure improvements. In 2006, it was reported that LIPA had pledged $20 million annually in grid improvements. But the reality proved to be substantially less–around $12.5 million–while LIPA also cut back on transmission line inspections.

Amidst the current turmoil, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has been highly critical of LIPA, calling for the “removal of management” for the “colossal misjudgments” that led to the utility’s failures. Cuomo made similar statements about LIPA and its private, for-profit subcontractor, National Grid, last year after Hurricane Irene. But as another day mercifully dawned on tens of thousands of homes still without electricity over two weeks after Sandy moved inland, the dysfunctional structure in charge of the dysfunctional infrastructure remains largely unchanged.

Which, it must be noted, is especially vexing because Governor Cuomo should not be powerless when it came to making changes to the Long Island Power Authority.

It was Andrew’s father, Governor Mario Cuomo, who oversaw the creation of LIPA in 1985 to clean up the fiscal and physical failures of the Long Island Lighting Company. LILCO’s inability to quickly restore power to hundreds of thousands of customers after Hurricane Gloria met with calls for change quite similar to contemporary outrage. But it was LILCO’s crushing debt that perhaps exacerbated problems with post-Gloria cleanup and absolutely precipitated the government takeover.

The best-laid schemes

It was April 1965 when LILCO’s president announced plans for Long Island’s first commercial nuclear power facility to be built on Long Island Sound near the town of Brookhaven, already home to a complex of research reactors. The 540-megawatt General Electric boiling water reactor (similar in design to those that failed last year in Japan) was estimated to cost $65 million and come online in 1973.

The price of the Shoreham nuclear project quickly ballooned, first, as LILCO proposed additional reactors across Long Island–none of which were ever built–and then as the utility up-rated the original design to 820 megawatts. Further design changes, some mandated by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and construction delays pushed the price tag to $2 billion by the late 1970s.

Because of its proximity to the Brookhaven reactors, LILCO expected little public activism against Shoreham, but local opposition steadily grew throughout the ’70s. The Sierra Club, the Audubon Society and environmentalist Barry Commoner all raised early objections. After a meltdown at Pennsylvania’s Three Mile Island nuclear plant in 1979, Shoreham saw 15,000 gather in protest outside its gates, an action that resulted in 600 arrests.

Three Mile Island led to new NRC rules requiring nuclear facilities to coordinate with civic authorities on emergency plans for accidents necessitating the evacuation of surrounding communities. LILCO was forced to confront the fact that, for Shoreham, the only routes for evacuation were already clogged highways that bottlenecked at a few bridges into Manhattan, 60 miles to the west.

In 1983, the government of Suffolk County, where Shoreham was located, determined that there was no valid plan for evacuating its population. New York Governor Mario Cuomo followed suit, ordering state regulators not to approve the LILCO-endorsed evacuation plan.

Still, as Shoreham’s reactor was finally completed in 1984, 11 years late and nearly 100-times over budget, the NRC granted LILCO permission for a low-power test.

But 1985’s Hurricane Gloria further eroded trust in LILCO, and the next year, the Chernobyl disaster further galvanized opposition to a nuclear plant. As LILCO’s debts mounted, it became apparent that a new structure was needed to deliver dependable power to Long Island residents.

The power to act

The Long Island Power Act of 1985 created LIPA to assume LILCO’s assets, and a subsidiary of this municipal authority, also known as LIPA, acquired LILCO’s electric transmission and distribution systems a year later. The radioactive but moribund Shoreham plant was purchased by the state for one dollar, and later decommissioned at a cost of $186 million. (Shoreham’s turbines were sent to Ohio’s Davis-Besse nuclear facility; its nuclear fuel was sent to the Limerick Nuclear Power Plant, with LILCO/LIPA paying Philadelphia Electric Company $50 million to take the fuel off its hands.)

The $6 billion Shoreham folly was passed on to consumers in the form of a three-percent surcharge on utility bills, to be charged for 30 years. Service on LILCO’s $7 billion in debt, half of which is a direct result of Shoreham, makes up 16 percent of every LIPA bill.

But LIPA itself is not really a utility company. Its roughly 100 employees are low on public utilities experience and, as the New York Times reports, high on political patronage. The majority of LILCO’s non-nuclear power plants were sold to a newly created company called KeySpan (itself a product of a merger of LILCO holdings with Brooklyn Union Gas), and maintenance of LIPA’s grid was subcontracted to KeySpan.

KeySpan was in turn purchased by British power company National Grid in 2006.

The situation is now further complicated, as National Grid lost out to Public Service Enterprise Group, New Jersey’s largest electricity provider, in a bid to continue its maintenance contract. PSEG takes over the upkeep of LIPA’s grid in 2014.

A commission on transmission

On Tuesday, Governor Cuomo the Younger announced formation of a Moreland Commission–a century-old New York State provision that allows for an investigative body with subpoena power–to explore ways of reforming or restructuring LIPA, including the possibility of integrating with the state’s New York Power Authority. And just hours later, LIPA’s COO and acting CEO, Michael Hervey, announced he would leave the utility at the end of the year.

But the problems look more systemic than one ouster or one commission, no matter how august, can correct. Andrew Cuomo’s inability to appoint new LIPA board members could owe as much to entrenched patronage practices as to political pre-positioning. State Republicans, overwhelmingly the beneficiaries of LIPA posts, are engaged in a behind-the-scenes standoff with the Democratic Governor over whom to name as a permanent LIPA director. Others see Cuomo as too willing to accept the political cover conveyed by not having his appointees take control of the LIPA board.

Still, no matter who runs LIPA, the elaborate public-private Russian-doll management structure makes accountability, not to mention real progress, hard to fathom. Perhaps it would be crazy to expect anything but regular disasters from a grid maintained by a foreign-owned, lame-duck, for-profit corporation under the theoretical direction of a leaderless board of political appointees, funded by some of the highest electricity rates in the country. And those rates, by the way, are not subject to the same public utilities commission oversight that would regulate a private utility, nor do they seem sensitive to any democratic checks and balances.

And all of this was created to bail out a utility destabilized by the money pit that is nuclear power.

The truth has consequences

As nighttime temperatures dip below freezing, it will be cold comfort, indeed, for those still without the power to light or heat their homes to learn that money they have personally contributed to help LIPA with its nuclear debt could have instead paid for the burying of vulnerable transmission lines and the storm-proofing of electrical transformers. But the unfortunate results of that trade-off hold a message for the entire country.

It was true (if not obvious) in 1965, it was true in 1985, and it is still true today: nuclear power, beyond being dirty and dangerous, is an absurdly expensive way to generate electricity. This is especially apropos now, in the wake of a superstorm thought to be a harbinger of things to come as the climate continues to warm.

In recent years, the nuclear industry has latched on to global warming as its latest raison d’être, claiming, quite inaccurately, that nuclear is a low-greenhouse gas answer to growing electrical needs. While the entire lifecycle of nuclear power is decidedly not climate friendly, it is perhaps equally as important to consider that nuclear plants take too long and cost too much to build. The time, as well as the federal and consumer dollars, would be better spent on efficiency, conservation, and truly renewable, truly climate-neutral energy projects.

That is not a hypothetical; that is the lesson of LIPA, and the unfortunate reality–still–for far too many New York residents.

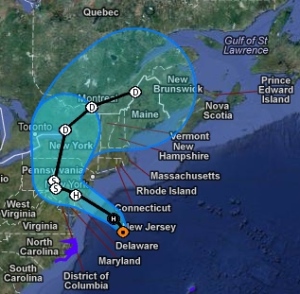

Oyster Creek Nuclear Alert: As Floodwaters Fall, More Questions Arise

New Jersey’s Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station remains under an official Alert, a day-and-a-half after the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission declared the emergency classification due to flooding triggered by Hurricane Sandy. An Alert is the second category on the NRC’s four-point emergency scale. Neil Sheehan, a spokesman for the federal regulator, said that floodwaters around the plant’s water intake structure had receded to 5.7 feet at 2:15 PM EDT Tuesday, down from a high of 7.4 feet reached just after midnight.

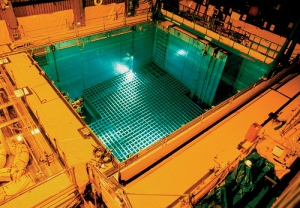

Water above 6.5 to 7 feet was expected to compromise Oyster Creek’s capacity to cool its reactor and spent fuel pool, according to the NRC. An “Unusual Event,” the first level of emergency classification, was declared Monday afternoon when floodwaters climbed to 4.7 feet.

Though an emergency pump was brought in when water rose above 6.5 feet late Monday, the NRC and plant owner Exelon have been vague about whether it was needed. As of this writing, it is still not clear if Oyster Creek’s heat transfer system is functioning as designed.

As flooding continued and water intake pumps were threatened, plant operators also floated the idea that water levels in the spent fuel pool could be maintained with fire hoses. Outside observers, such as nuclear consultant Arnie Gundersen, suspected Oyster Creek might have accomplished this by repurposing its fire suppression system (and Reuters later reported the same), though, again, neither Exelon nor regulators have given details.

Whether the original intake system or some sort of contingency is being used, it appears the pumps are being powered by backup diesel generators. Oyster Creek, like the vast majority of southern New Jersey, lost grid power as Sandy moved inland Monday night. In the even of a site blackout, backup generators are required to provide power to cooling systems for the reactor–there is no such mandate, however, for spent fuel pools. Power for pool cooling is expected to come either from the grid or the electricity generated by the plant’s own turbines.

As the NRC likes to remind anyone who will listen, Oyster Creek’s reactor was offline for fueling and maintenance. What regulators don’t add, however, is that the reactor still needs cooling for residual decay heat, and that the fuel pool likely contains more fuel and hotter fuel as a result of this procedure, which means it is even more at risk for overheating. And, perhaps most notably, with the reactor shutdown, it is not producing the electricity that could be used to keep water circulating through the spent fuel pool.

If that sounds confusing, it is probably not by accident. Requests for more and more specific information (most notably by the nuclear watchdog site SimplyInfo) from Exelon and the NRC remain largely unanswered.

Oyster Creek was not the only nuclear power plant dealing with Sandy-related emergencies. As reported here yesterday, Nine Mile Point Unit 1 and Indian Point Unit 3–both in New York–each had to scram because of grid interruptions triggered by Monday’s superstorm. In addition, one of New Jersey’s Salem reactors shut down when four of six condenser circulators (water pumps that aid in heat transfer) failed “due to a combination of high river level and detritus from Hurricane Sandy’s transit.” Salem vented vapor from what are considered non-nuclear systems, though as noted often, that does not mean it is completely free of radioactive components. (Salem’s other reactor was offline for refueling.)

Limerick (PA) reactors 1 and 2, Millstone (CT) 3, and Vermont Yankee all reduced power output in response to Superstorm Sandy. The storm also caused large numbers of emergency warning sirens around both Oyster Creek and the Peach Bottom (PA) nuclear plant to fail.

If you thought all of these problems would cause nuclear industry representatives to lay low for a while, well, you’d be wrong:

“Our facilities’ ability to weather the strongest Atlantic tropical storm on record is due to rigorous precautions taken in advance of the storm,” Marvin Fertel, chief executive officer of the Nuclear Energy Institute, a Washington-based industry group, said yesterday in a statement.

Fertel went on to brag that of the 34 reactors it said were in Sandy’s path, 24 survived the storm without incident.

Or, to look at it another way, during a single day, the heavily populated eastern coast of the Unite States saw multiple nuclear reactors experience problems. And that’s in the estimation of the nuclear industry’s top lobbyist.

Or, should we say, the underestimation? Of the ten reactors not in Fertel’s group of 24, seven were already offline, and the industry is not counting them. So, by Fertel’s math, Oyster Creek does not figure against what he considers success. Power reductions and failed emergency warning systems are also not factored in, it appears.

This storm–and the trouble it caused for America’s nuclear fleet–comes in the context of an 18-month battle to improve nuclear plant safety in the wake of the multiple meltdowns and continuing crisis at Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear facility. Many of the rules and safety upgrades proposed by a US post-Fukushima taskforce are directly applicable to problems resulting from Superstorm Sandy. Improvements to flood preparation, backup power regimes, spent fuel storage and emergency notification were all part of the taskforce report–all of which were theoretically accepted by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. But nuclear industry pushback, and stonewalling, politicking and outright defiance by pro-industry commissioners has severely slowed the execution of post-Fukushima lessons learned.

The acolytes of atom-splitting will no doubt point to the unprecedented nature of this massive hybrid storm, echoing the “who could have predicted” language heard from so many after the earthquake and tsunami that started the Fukushima disaster. Indeed, such language has already been used–though, granted, in a non-nuclear context–by Con Edison officials discussing massive power outages still afflicting New York City:

At a Consolidated Edison substation in Manhattan’s East Village, a gigantic wall of water defied elaborate planning and expectations, swamped underground electrical equipment, and left about 250,000 lower Manhattan customers without power.

Last year, the surge from Hurricane Irene reached 9.5 feet at the substation. ConEd figured it had that covered.

The utility also figured the infrastructure could handle a repeat of the highest surge on record for the area — 11 feet during a hurricane in 1821, according to the National Weather Service. After all, the substation was designed to withstand a surge of 12.5 feet.

With all the planning, and all the predictions, planning big was not big enough. Sandy went bigger — a surge of 14 feet.

“Nobody predicted it would be that high,” said ConEd spokesman Allan Drury.

In a decade that has seen most of the warmest years on record and some of the era’s worst storms, there needs to be some limit on such excuses. Nearly a million New York City residents (including this reporter) are expected to be without electricity through the end of the week. Residents in the outer boroughs and millions in New Jersey could be in the dark for far longer. Having a grid that simply survives a category 1 hurricane without a Fukushima-sized nuclear disaster is nothing to crow about.

The astronomical cost of restoring power to millions of consumers is real, as is the potential danger still posed by a number of crippled nuclear power plants. The price of preventing the current storm-related emergencies from getting worse is also not a trivial matter, nor are the radioactive isotopes vented with every emergency reactor scram. All of that should be part of the nuclear industry’s report card; all of that should raise eyebrows and questions the next time nuclear is touted as a clean, safe, affordable energy source for a climate change-challenged world.

UPDATE: The AP is reporting that the NRC has now lifted the emergency alert at Oyster Creek.

Superstorm Sandy Shows Nuclear Plants Who’s Boss

Once there was an ocean liner; its builders said it was unsinkable. Nature had other ideas.

On Monday evening, as Hurricane Sandy was becoming Post-Tropical Cyclone Sandy, pushing record amounts of water on to Atlantic shores from the Carolinas to Connecticut, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission issued a statement. Oyster Creek, the nation’s oldest operating nuclear reactor, was under an Alert. . . and under a good deal of water.

An Alert is the second rung on the NRC’s four-point emergency classification scale. It indicates “events are in process or have occurred which involve an actual or potential substantial degradation in the level of safety of the plant.” (By way of reference, the fourth level–a General Emergency–indicates substantial core damage and a potential loss of containment.)

As reported earlier, Oyster Creek’s coolant intake structure was surrounded by floodwaters that arrived with Sandy. Oyster Creek’s 47-year-old design requires massive amounts of external water that must be actively pumped through the plant to keep it cool. Even when the reactor is offline, as was the case on Monday, water must circulate through the spent fuel pools to keep them from overheating, risking fire and airborne radioactive contamination.

With the reactor shut down, the facility is dependant on external power to keep water circulating. But even if the grid holds up, rising waters could trigger a troubling scenario:

The water level was more than six feet above normal. At seven feet, the plant would lose the ability to cool its spent fuel pool in the normal fashion, according to Neil Sheehan, a spokesman for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

The plant would probably have to switch to using fire hoses to pump in extra water to make up for evaporation, Mr. Sheehan said, because it could no longer pull water out of Barnegat Bay and circulate it through a heat exchanger, to cool the water in the pool.

If hoses desperately pouring water on endangered spent fuel pools remind you of Fukushima, it should. Oyster Creek is the same model of GE boiling water reactor that failed so catastrophically in Japan.

The NRC press release (PDF) made a point–echoed in most traditional media reports–of noting that Oyster Creek’s reactor was shut down, as if to indicate that this made the situation less urgent. While not having to scram a hot reactor is usually a plus, this fact does little to lessen the potential problem here. As nuclear engineer Arnie Gundersen told Democracy Now! before the Alert was declared:

[Oyster Creek is] in a refueling outage. That means that all the nuclear fuel is not in the nuclear reactor, but it’s over in the spent fuel pool. And in that condition, there’s no backup power for the spent fuel pools. So, if Oyster Creek were to lose its offsite power—and, frankly, that’s really likely—there would be no way cool that nuclear fuel that’s in the fuel pool until they get the power reestablished. Nuclear fuel pools don’t have to be cooled by diesels per the old Nuclear Regulatory Commission regulations.

A site blackout (SBO) or a loss of coolant issue at Oyster Creek puts all of the nuclear fuel and high-level radioactive waste at risk. The plant being offline does not change that, though it does, in this case, increase the risk of an SBO.

But in the statement from the NRC, there was also another point they wanted to underscore (or one could even say “brag on”): “As of 9 p.m. EDT Monday, no plants had to shut down as a result of the storm.”

If only regulators had held on to that release just one more minute. . . .

SCRIBA, NY – On October 29 at 9 p.m., Nine Mile Point Unit 1 experienced an automatic reactor shutdown.

The shutdown was caused by an electrical grid disturbance that caused the unit’s output breakers to open. When the unit’s electrical output breakers open, there is nowhere to “push” or transmit the power and the unit is appropriately designed to shut down under these conditions.

“Our preliminary investigation identified a lighting pole in the Scriba switchyard that had fallen onto an electrical component. This is believed to have caused the grid disturbance. We continue to evaluate conditions in the switchyard,” said Jill Lyon, company spokesperson.

Nine Mile Point Nuclear Station consists of two GE boiling water reactors, one of which would be the oldest operating in the US were it not for Oyster Creek. They are located just outside Oswego, NY, on the shores of Lake Ontario. Just one week ago, Unit 1–the older reactor–declared an “unusual event” as the result of a fire in an electrical panel. Then, on Monday, the reactor scrammed because of a grid disturbance, likely caused by a lighting pole knocked over by Sandy’s high winds.

An hour and forty-five minutes later, and 250 miles southeast, another of the nation’s ancient reactors also scrammed because of an interruption in offsite power. Indian Point, the very old and very contentious nuclear facility less than an hour’s drive north of New York City, shut down because of “external grid issues.” And Superstorm Sandy has given Metropolitan New York’s grid a lot of issues.

While neither of these shutdowns is considered catastrophic, they are not as trivial as the plant operators and federal regulators would have you believe. First, emergency shutdowns–scrams–are not stress-free events, even for the most robust of reactors. As discussed here before, it is akin to slamming the breaks on a speeding locomotive. These scrams cause wear and tear aging reactors can ill afford.

Second, scrams produce pressure that usually leads to the venting of some radioactive vapor. Operators and the NRC will tell you that these releases are well within “permissible” levels–what they can’t tell you is that “permissible” is the same as “safe.”

If these plants were offline, or running at reduced power, the scrams would not have been as hard on the reactors or the environment. Hitting the breaks at 25 mph is easier on a car than slamming them while going 65. But the NRC does not have a policy of ordering shutdowns or reductions in capacity in advance of a massive storm. In fact, the NRC has no blanket protocol for these situations, period. By Monday morning, regulators agreed to dispatch extra inspectors to nuclear plants in harm’s way (and they gave them sat phones, too!), but they left it to private nuclear utility operators to decide what would be done in advance to prepare for the predicted natural disaster.

Operators and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission spokes-folks like to remind all who will listen (or, at least, all who will transcribe) that nuclear reactors are the proverbial house of bricks–a hurricane might huff and puff, but the reinforced concrete that makes up a typical containment building will not blow in. But that’s not the issue, and the NRC, at least, should know it.

Loss of power (SBOs) and loss of coolant accidents (LOCAs) are what nuclear watchdogs were warning about in advance of Sandy, and they are exactly the problems that presented themselves in New York and New Jersey when the storm hit.

The engineers of the Titanic claimed that they had built the unsinkable ship, but human error, corners cut on construction, and a big chunk of ice cast such hubris asunder. Nuclear engineers, regulators and operators love to talk of four-inch thick walls and “defense-in-depth” backup systems, but the planet is literally littered with the fallout of their folly. Nuclear power systems are too complex and too dangerous for the best of times and the best laid plans. How are they supposed to survive the worst of times and no plans at all?

Hurricane Sandy Brings Wind, Rain and Irony to US Nuclear Plants

With Hurricane Sandy projected to make landfall hundreds of miles to the south and the predicted storm surge still over 24 hours away, New York City completely shuttered its mass transit system early Sunday evening. By 7 PM, all subway service was halted for only the second time in history. The fear, according to state authorities, is that heavy rainfall or the expected six-to-eleven-foot increase in tide levels would flood subway tunnels, stranding trains at various points across the 842 miles of track.

Fearing similar flooding, the Washington, DC, Metro is also expected to suspend service for all of Monday.

Twelve hours after NYC shut down its subways, at 7 AM Monday, with Hurricane Sandy lashing the Mid-Atlantic coast with heavy rain and 85 mph winds, at least a half-dozen commercial nuclear reactors lie in the storm’s projected path–and the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission has yet to issue any specific orders to the facilities it supposedly oversees. In fact, check out the NRC’s twitter feed or look at its website, and the only reference you will find to what has been dubbed “Frankenstorm” is the recently posted cancellation notice for a public hearing that was supposed to convene on Tuesday, October 30.

The subject of that meeting? The Fort Calhoun Nuclear Generating Station.

The Fort Calhoun plant sits on the Missouri River, on the eastern edge of Nebraska, near the town of Blair. Fort Calhoun’s single pressurized water reactor was shutdown for refueling in April of last year, but floods during the summer of 2011 encircled the facility and caused a series of dangerous incidents. A breach in water berms surrounded transformers and auxiliary containment buildings with two feet of water. Around that same time, a fire shut down power to Fort Calhoun’s spent fuel pools, stopping the circulation of cooling water for 90 minutes and triggering a “red event,” the second most severe classification. Outside of its reactor, the Nebraska facility is home to approximately 800,000 pounds of high-level radioactive waste. To this day, Fort Calhoun is offline and awaiting further evaluation by the NRC.

That a hearing on a flooded plant has been postponed because of the threat of flooding near NRC offices seems like the height of irony, but it pales next to the comparison of safety preparedness measures taken by New York’s Metropolitan Transit Authority for a subway and the federal government’s approach to a fleet of nuclear reactors.

That is not to say that the NRC is doing nothing. . . not exactly. Before the weekend, regulators let it be known that they were considering sending extra inspectors to some nuclear facilities in Sandy’s path. Additionally, regional officials stressed that plant operators were doing walk downs to secure any outside equipment that might become a sort of missile in the event of high winds. It is roughly the equivalent of telling homeowners to tie down their lawn furniture.

And it seems to be understood, at least at the nuclear plants in southern New Jersey, that reactors should be shutdown at least two hours before winds reach 74 mph.

To all that, the NRC made a point of assuring the public that reactor containment buildings could withstand hurricane-force winds, or any odd piece of “lawn furniture” that might be hurled at them.

That’s nice, but hardly the point.

Containment breech is always a concern, but it is not the main issue today. A bigger worry are SBOs–Station Black Outs–loss-of-power incidents that could impede a plant’s capacity to cool its reactors or spent fuel pools, or could interfere with operators’ ability to monitor everything that is going on inside those areas.

As reported last year, Hurricane Irene caused an emergency shutdown at Maryland’s Calvert Cliffs nuclear plant when aluminum siding torn off by high winds shorted out the main transformer and caused an explosion, damaging structures and equipment. Calvert Cliffs was one of the facilities that had chosen not to reduce output or shutdown in advance of Irene–especially alarming because just days before that storm, plant operators had reported trouble with its diesel backup generators.

Irene caused other problems, beyond loss of electricity to millions of consumers, public notification sirens in two emergency preparedness zones were disabled by the storm.

In sum, storm damage triggered a scram at a plant with faulty backup generators. If power had not been restored, backup would have failed, and the rising temperatures in the reactors and fuel pools would have necessitated an evacuation of the area–only evacuation would have been hampered because of widespread power outages and absent sirens.

The worst did not happen last year at Calvert Cliffs, but the damage sustained there was substantial, and the incident should serve as a cautionary tale. Shutting down a nuclear reactor doesn’t prevent every problem that could result from a severe storm, but it narrows the possibilities, reduces some dangers, and prevents the excessive wear and tear an emergency shutdown inflicts on an aging facility.

Calvert Cliffs is again in the line of fire–as are numerous other plants. Hurricane Sandy will likely bring high winds, heavy rain and the threat of flooding to nuclear facilities in Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey, New York and Connecticut. Given last year’s experiences–and given the high likelihood that climate change will bring more such events in years to come–it might have been expected that the NRC would have a more developed policy.

Instead, as with last year’s Atlantic hurricane, federal regulators have left the final decisions to private sector nuclear operators–operators that have a rather poor track record in evaluating threats to public safety when actions might affect their bottom line.

At the time of this writing, the rain in New York City is little more than a drizzle, winds are gusting far below hurricane strength, and high tide is still over ten hours away. Hurricane Sandy is over 300 miles to the south.

But Gotham is a relative ghost town. The subway turnstiles are locked; city busses are nowhere to be seen.

At the region’s nuclear facilities, however–at North Anna, Hope Creek, Salem and Oyster Creek, at Calvert Cliffs, Indian Point and Millstone–there is no such singular sense of better-safe-than-sorry mission.

In New York, it can be argued that the likes of Governor Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Michael Bloomberg have gone overboard, that they have made decisions based not just on safety, but on fears of political fallout and employee overtime. But in the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s northeast region, there is no chance of that kind of criticism–one might even say there is no one to criticize, because it would appear that there is no one in charge.

NRC Halts License Approvals Pending New Guidelines on Nuclear Waste

The US Nuclear Regulatory Commission announced Tuesday it would suspend the issuing of new reactor operating licenses, license renewals and construction licenses until the agency crafted a plan for dealing with the nation’s growing spent nuclear fuel crisis. The action comes in response to a June ruling by the US Court of Appeals that found the NRC’s “Waste Confidence Decision”–the methodology used to evaluate the dangers of nuclear waste storage–was wholly inadequate and posed a danger to public health and the environment.

Prior to the court’s ruling, the Commission had evaluated licensing and relicensing with the assumption that spent fuel–currently stored on site at nuclear power plants in pools and dry casks–would soon be moved to a central long-term waste repository. As previously noted, that option was once thought to be Yucca Mountain, but after years of preliminary work and tens of millions of dollars wasted, Yucca was found to be a poor choice, and the Obama Department of Energy and the NRC ended the project. The confirmation of new NRC Chair Allison Macfarlane–considered a nuclear waste expert and on record as a Yucca Mountain critic–focused even more attention on the country’s lack of realistic plans for safe, permanent waste storage.

The release from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission [PDF] put it this way:

Waste confidence undergirds certain agency licensing decisions, in particular new reactor licensing and reactor license renewal.

Because of the recent court ruling striking down our current waste confidence provisions, we are now considering all available options for resolving the waste confidence issue, which could include generic or site-specific NRC actions, or some combination of both. We have not yet determined a course of action.

In recognition of our duties under the law, we will not issue licenses dependent upon the Waste Confidence Decision or the Temporary Storage Rule until the court’s remand is appropriately addressed.

What this means in real terms remains to be seen. No licenses or renewals were thought imminent. Next up were likely a decision on extending the life of Indian Point, a short drive north of New York City, and a Construction and Operation License for Florida’s Levy County project, but neither was expected before sometime next year. Officially, 19 final reactor decisions are now on hold, though the NRC stressed that “all licensing reviews and proceedings should continue to move forward.”

Still, this should be read as a victory for the originators of the suit that resulted in the June ruling–the Attorneys General of Connecticut, New Jersey, New York and Vermont in coordination with the Prairie Island Indian Community of Minnesota and environmental groups represented by the National Resources Defense Council–and most certainly for the millions of Americans that live close to nuclear plants and their large, overstuffed, under-regulated pools of dangerous nuclear waste. Complainants not only won the freeze on licensing, the NRC guaranteed that any new generic waste rule would be open to public comment and environmental assessment or environmental impact studies, and that site-specific cases would be subject to a minimum 60-day consideration period.

While there is still plenty of gray area in that guarantee, the NRC has (under pressure) made the process more transparent than most similar dealings at the agency. The commission has also, at least for the moment, formally acknowledged that the nation’s nuclear reactor fleet faces a very pressing problem.

The US has 72,000 tons of radioactive waste and generates an additional 2,000 tons every year. Spent fuel pools at individual sites are already so full they pose numerous threats, some eerily similar to the ongoing disaster at Fukushima. Dry cask storage poses other problems and much additional expense. And regional interim waste storage facilities, an idea possibly favored by Macfarlane, is problematic for many reasons, not the least of which is that no sites have yet been designated or built.

But nuclear plant operators, already burdened by the spiraling costs of a poorly maintained and aging inventory, are desperate to have the federal government take the waste problem off their backs–and off their books. Whether that is even technically feasible, let alone politically of fiscally possible, remains to be seen. But the NRC has at least recognized–or at least been forced to recognize–that the nuclear industry should not be allowed to create waste indefinitely without a plan to safely secure what is already on hand.

Emergency Evacuation, Drill Requirements Quietly Cut While Nuclear Regulators Consider Doubling Length of License Extensions

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission will hold a public meeting tonight (Thursday, May 17) on the safety and future of the Indian Point Energy Center (IPEC), a nuclear power plant located in Buchanan, NY, less than 40 miles north of New York City. The Tarrytown, NY “open house” (as it is billed) is designed to explain and answer questions about the annual assessment of safety at IPEC delivered by the NRC in March, but will also serve as a forum where the community can express its concerns in advance of the regulator’s formal relicensing hearings for Indian Point, expected to start later this year.

And if you are in the area–even as far downwind as New York City–you can attend (more on this at the end of the post).

Why might you want to come between Entergy, the current owner of Indian Point, and a shiny new 20-year license extension? As the poets say, let me count the ways:

Indian Point has experienced a series of accidents and “unusual events” since its start that have often placed it on a list of the nation’s worst nuclear power plants. Its structure came into question within months of opening; it has flooded with 100,000 gallons of Hudson River water; it has belched hundreds of thousands of gallons of radioactive steam in the last 12 years; its spent fuel pools have leaked radioactive tritium, strontium 90 and nickel 63 into the Hudson and into groundwater; and IPEC has had a string of transformer fires and explosions, affecting safety systems and spilling massive amounts of oil into the Hudson.

That poor, poor Hudson River. Indian Point sits on its banks because it needs the water for cooling, but beyond the radioactive leaks and the oil, the water intake system likely kills nearly a billion aquatic organisms a year. And the overheated exhaust water is taking its toll on the river, as well.

Indian Point is located in a seismically precarious place, right on top of the intersection of the Stamford-Peekskill and Ramapo fault lines. The NRC’s 2010 seismic review places IPEC at the top of the list of reactors most at risk for earthquake damage.

Entergy was also late in providing the full allotment of new warning sirens within the 10-mile evacuation zone, which is a kind of “insult to injury” shortfall, since both nuclear power activists and advocates agree that Indian Point’s evacuation plan, even within the laughably limited “Plume Exposure Pathway Emergency Planning Zone,” is more fantasy than reality.

With this kind of legacy, and all of these ongoing problems, it would seem, especially in a world informed by the continuing Fukushima disaster, that the NRC’s discretionary right to refuse a new operating license for Indian Point would be the better part of valor. But the NRC rarely bathes itself in such glory.

Instead, when the nuclear industry meets rules with which it cannot comply, the answer has usually been for the regulatory agencies to just change the rules.

Such was the case the night before the-night-before-Christmas, when the NRC and the Federal Emergency Management Agency quietly changed long-standing emergency planning requirements:

Without fanfare, the nation’s nuclear power regulators have overhauled community emergency planning for the first time in more than three decades, requiring fewer exercises for major accidents and recommending that fewer people be evacuated right away.

Nuclear watchdogs voiced surprise and dismay over the quietly adopted revamp — the first since the program began after Three Mile Island in 1979. Several said they were unaware of the changes until now, though they took effect in December.

At least four years in the works, the changes appear to clash with more recent lessons of last year’s reactor crisis in Japan. A mandate that local responders always run practice exercises for a radiation release has been eliminated — a move viewed as downright bizarre by some emergency planners.

The scope of the changes is rivaled only by the secrecy in which they were implemented. There were no news releases regarding the overhaul from either FEMA or the NRC in December or January. Industry watchdogs, such as the Nuclear Information and Resource Service, only learned about the new rules when questioned by the Associated Press.

It was the AP that published an in-depth investigation of lax nuclear regulation last June, and it was the AP that spotted this latest gift to the nuclear industry:

The latest changes, especially relaxed exercise plans for 50-mile emergency zones, are being flayed by some local planners and activists who say the widespread contamination in Japan from last year’s Fukushima nuclear accident screams out for stronger planning in the United States, not weaker rules.

FEMA officials say the revised standards introduce more variability into planning exercises and will help keep responders on their toes. The nuclear power industry has praised the changes on similar grounds.

Onsite security forces at nuclear power plants have practiced defending against make-believe assaults since 1991 and increased the frequency of these drills after the 2001 terrorist attacks. The new exercises for community responders took years to consider and adopt with prolonged industry and government consultations that led to repeated drafts. The NRC made many changes requested by the industry in copious comments.

Naturally.

But, if a nearby resident or a city official were to express concerns about a nuclear plant’s emergency preparedness–like, say, those that live and work around Indian Point–regulators would likely dismiss them as alarmist:

None of the revisions has been questioned more than the new requirement that some planning exercises incorporate a reassuring premise: that little or no harmful radiation is released. Federal regulators say that conducting a wider variety of accident scenarios makes the exercises less predictable.

However, many state and local emergency officials say such exercises make no sense in a program designed to protect the population from radiation released by a nuclear accident.

“We have the real business of protecting public health to do if we’re not needed at an exercise,” Texas radiation-monitoring specialist Robert Free wrote bluntly to federal regulators when they broached the idea. “Not to mention the waste of public monies.”

Environmental and anti-nuclear activists also scoffed. “You need to be practicing for a worst case, rather than a nonevent,” said nuclear policy analyst Jim Riccio of the group Greenpeace.

From the perspective of the industry-captured regulators, if you can’t handle the truth, rewrite the truth. And if there were any doubt about the motives of the nuclear industry, itself, when it comes to these new rules, a reading of the AP report makes it clear: from top to bottom, the revisions require less of nuclear operators.

While officials stress the importance of limiting radioactive releases, the revisions also favor limiting initial evacuations, even in a severe accident. Under the previous standard, people within two miles would be immediately evacuated, along with everyone five miles downwind. Now, in a large quick release of radioactivity, emergency personnel would concentrate first on evacuating people only within two miles. Others would be told to stay put and wait for a possible evacuation order later.

This rule change feels ludicrous in the wake of Fukushima, where a 12-mile radius is assumed to be a no-go zone for a generation, and the State Department advised US citizens to evacuate beyond 50 miles, but it is especially chilling in the context of Indian Point. The stated reasoning behind the tiny evacuation zone is that anything broader would be impossible to execute quickly, so better to have folks just “hunker down.”

“They’re saying, ‘If there’s no way to evacuate, then we won’t,'” Phillip Musegaas, a lawyer with the environmental group Riverkeeper, said of the stronger emphasis on taking shelter at home. The group is challenging relicensing of Indian Point.

Over 17 million people live within 50 miles of IPEC. In February, environmental and anti-nuclear groups asked the NRC to expand evacuation planning to 25 miles from the current 10, and to push readiness zones out to 100 miles, up from 50. They also asked for emergency planners to take into account multiple disasters, like those experienced last year in Japan.

That might have been an opportune time for the regulators to explain that they had already changed the rules–two months earlier–and that they had not made them stronger, they had made them weaker. Not only will the 10 and 50-mile zones remain as they are, the drills for the 50-mile emergency will be required only once every eight years–up from the current six-year cycle.

With the turnover in elected officials and municipal employees being what it is–especially in times of constricting local budgets–even a run-through every six years seems inadequate. An eight-year lag is criminal. (Perhaps the NRC can revise assumptions so that disasters only happen within a year or two of a readiness drill.)

But an extra two years between drills is cheaper. So is the concentration of the evacuation zone in case of quick radiation release. So are many of the other changes. At a time when regulators should look at Japan and ask “What more can we do?” they instead are falling over themselves to do less.

And the nuclear industry needs all the help it can get.

The fact is that without this kind of help–without the weakened rules and limp enforcement, without the accelerated construction and licensing arrangements, without the federal loan guarantees and liability caps, and without the cooperation and expenditures of state and local governments–nuclear could not exist. Indeed, it would not exist, because without this wellspring of corporate welfare, nuclear power plants would never turn a profit for their owners.

In fact, with the cost of new plant construction escalating by the minute (the new AP1000 reactors approved for Georgia’s Plant Vogtle this February are already $900 million over budget), the strategy of energy giants like Entergy rests more on buying up old reactors and spending the bare minimum to keep them running while they apply for license extensions. This is the game plan for Indian Point. It is also Entergy’s plan for Vermont Yankee, a plant granted a license extension by the NRC in March, over the objections of the state government.

The case of Vermont Yankee is currently before a federal appeals court–and New York has filed an amicus brief on Vermont’s behalf, since New York Governor Andrew Cuomo would like to see Indian Point shuttered at the end of its current license, and it knows the NRC has never met a license extension it didn’t like.

Meanwhile, however, Entergy continues to hemorrhage money. The second largest nuclear power provider in the nation posted a first quarter loss of $151.7 million–its stock is down 13% this year–directly as a result of its creaky, inefficient, often offline nuclear reactors. It needs quick, cheap, easy relicensing for facilities like Indian Point if it is ever going to turn things around.

Although maybe not even then. Take, for example, the current plight of California’s San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station (SONGS). San Onofre’s two reactors have been offline since the end of January, when a radiation leak led to the discovery of accelerated wear in over 1,300 copper tubes used to move radioactive water to and from the plant’s recently replaced steam generators:

[Southern California] Edison finished installation of the $671-million steam generators less than two years ago, promising customers they would create major energy savings. Now, officials estimate it will cost as much as $65 million to fix the problems and tens of millions more to replace the lost power.

Both those figures are likely low. No one has yet isolated the exact cause of the wear, though attention focuses on excessive vibration (and that vibration will likely be linked to faulty design and the attempt to retrofit off-the-shelf parts on the cheap), and the time it will take to correct the problem, make repairs and get the reactors up to something close to full power is somewhere between unpredictable and never.

Indeed, Edison is instead talking about running SONGS at reduced capacity, at least for several months. Plant engineers say they believe running the reactors at lower power will minimize vibration (though critics point out this will not resolve the problems with already badly worn tubing), but the reality is much simpler. Every kilowatt the nuclear plant can manage to generate is one kilowatt that Edison won’t have to buy from someone else. There is some warranty coverage for the new generators, but there is none for the replacement costs of the electricity.

Edison will, of course, ask the California Public Utility Commission if it can pass replacement costs on to consumers, but that, in turn, begs another question. When the PUC approved the cost of replacing the steam generators, they did so with the assumption that SONGS would average 88% capacity until its license expires in 2022.

An analysis at the time showed that a one-year outage or a scenario in which the plant would run at lower capacity for an extended period could make the project a money loser. But the PUC found those scenarios to be unlikely and determined that the project would probably be a good deal for ratepayers.

“If the plant runs at 50 to 80 percent capacity for the rest of its life, the entire cost-effectiveness analysis is turned on its head,” said Matthew Freedman, attorney for advocacy group The Utility Reform Network.

Sound familiar?

Regulators, be they at the federal NRC or a state’s PUC, can re-imagine reality all they want, but reality turns out to be stubborn. . . and, it seems, costly.

And don’t think that the industry hasn’t already cottoned to this.

In the midst of a battle over extending the 40-year licenses of two Entergy Corp. nuclear plants near New York City, federal regulators are looking into whether such plants would be eligible for yet another extension.

That would mean the Indian Point plants and others around the county might still be running after reaching 60 years of age.

Bill Dean, a regional administrator for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, said Wednesday the agency “is currently looking at research that might be needed to determine whether there could be extensions even beyond” the current 60-year limit for licenses.

Yes, the article attributes the initiative to federal regulators, but it strains credulity to believe they came up with this idea on their own. The industry can do the money math–hell, it’s pretty much the only thing they do–extending a license for 40 years beyond design life has got to be more profitable than extending a license for only 20 years.

And let’s be clear about that. The design life of Generation II reactors–the BWRs and PWRs that make up the US nuclear power fleet–is 30 to 40 years. When the plans were drawn up for Indian Point, Vermont Yankee, San Onofre, or any of the other 98 reactors still more-or-less functioning around the country, the assumption was that they would be decommissioned after about four decades. Current relicensing gives these aged reactors another 20 years, but it now turns out that this is only an interim move, designed to buy time to rewrite the regulations and give reactors a full second life. Eighty years in total.

It is yet another example of how rules are shaped–and ignored–to protect the bottom line of the nuclear industry, and not the safety of US citizens. (Or, for that matter, the pocketbooks of US consumers.)

And so, it is yet another example of why the Nuclear Regulatory Commission cannot be allowed to continue its rubberstamp relicensing.

And this is where you come in: As mentioned at the top, the NRC’s Bill Dean (the same guy looking into doubling the license extensions) will be in Tarrytown, NY, along with other government and Entergy representatives to answer questions and listen to testimony about the past, present, and future of Indian Point.

The open house is from 6 to 8 PM, and the public meeting is from 7 to 9 PM at the DoubleTree Hotel Tarrytown, 255 South Broadway, Tarrytown, NY.

Riverkeeper, in coordination with Clearwater, NYPIRG, Citizens’ Awareness Network, Occupy Wall Street Environmental Working Group, IPSEC, Shut Down Indian Point Now, and others will be holding a press conference before the open house, at 5:30 PM.

If you live in New York City, Riverkeeper is sponsoring busses to Tarrytown. Busses leave at 3:45 PM sharp from Grand Central (busses will be waiting at 45th St. and Vanderbilt Ave.). More info from SDIPN here. Reserve a place on a bus through Riverkeeper here.

#M1GS: May Day Events Planned for New York City and Across US

If you are looking for something to do for May Day (yes, Virginia, that’s May 1, 2012), to support the called “General Strike,” to support Occupy Wall Street, or to join with your favorite band of labor brothers and sisters, take a gander at these comprehensive lists:

If you are still wondering why you should get out there, you haven’t been paying attention. Whether you are upset about financial fraud, mortgage fraud, the constricting domestic economy, your constricting civil rights or the folly and carnage of foreign wars (declared or undeclared), there’s a place for you this May Day. There is much to be done, but as I and the New York Times observed last fall, “the public airing of grievances is a legitimate and important end in itself.”

What, not enough? Remember that May Day is an American holiday, created by and for American workers to demand improved conditions, basic respect, and fairer access to the wealth of a prosperous nation. Times have changed, but a quick google of “Madison, WI,” “Benton Harbor, MI,” “Ohio Recall,” “CAFTA,” KORUS,” or “foreclosure fraud” coupled with practically any community you know will tell you the struggle is far from over.

Need a little more context? Try this quick history of May Day. Need a little more inspiration? Here are one, two rundowns of some of what is set for Tuesday.

And this is important to remember: May 1 is not the beginning of our fight, and it is not the end of our fight. May 1 isn’t the only day we fight, and it is not the only way we fight–it is just one day and one way in which we fight together.

Now go forth. . . and #occupy!

Occupy Wall Street for Dummies – Lesson 1

(photo credits: The People’s Mic – Gregg Levine; NOT the People’s Mike – aboutmattlaw)

(photo credits: The People’s Mic – Gregg Levine; NOT the People’s Mike – aboutmattlaw)

Oakland Mayor Jean Quan Admits Cities Coordinated Crackdown on Occupy Movement

Embattled Oakland Mayor Jean Quan, speaking in an interview with the BBC (excerpted on The Takeaway radio program–audio of Quan starts at the 5:30 mark), casually mentioned that she was on a conference call with leaders of 18 US cities shortly before a wave of raids broke up Occupy Wall Street encampments across the country. “I was recently on a conference call with 18 cities across the country who had the same situation. . . .”

Mayor Quan then rambles about how she “spoke with protestors in my city” who professed an interest in “separating from anarchists,” implying that her police action was helping this somehow.

Interestingly, Quan then essentially advocates that occupiers move to private spaces, and specifically cites Zuccotti Park as an example:

In New York City, it’s interesting that the Wall Street movement is actually on a private park, so they’re not, again, in the public domain, and they’re not infringing on the public’s right to use a public park.

Many witnesses to the wave of government crackdowns on numerous #occupy encampments have been wondering aloud if the rapid succession was more than a coincidence; Jean Quan’s casual remark seems to clearly imply that it was.

Might it also be more than a coincidence that this succession of police raids started after President Obama left the US for an extended tour of the Pacific Rim?

You must be logged in to post a comment.