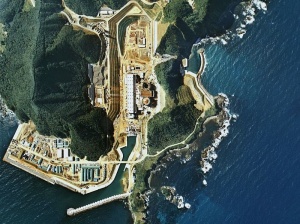

(photo: JanneM)

Late Thursday, the United States Coast Guard reported that they had successfully scuttled the Ryou-Un Maru, the Japanese “Ghost Ship” that had drifted into US waters after being torn from its moorings by the tsunami that followed the Tohoku earthquake over a year ago. The 200-foot fishing trawler, which was reportedly headed for scrap before it was swept away, was seen as potentially dangerous as it drifted near busy shipping lanes.

Coincidentally, the “disappearing” of the Ghost Ship came during the same week the Congressional Research Service (CRS) released its report on the effects of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster on the US marine environment, and, frankly, the metaphor couldn’t be more perfect. The Ryou-Un Maru is now resting at the bottom of the ocean–literally nothing more to see there, thanks to a few rounds from a 25mm Coast Guard gun–and the CRS hopes to dispatch fears of the radioactive contamination of US waters and seafood with the same alacrity.

But while the Ghost Ship was not considered a major ecological threat (though it did go down with around 2,000 gallons of diesel fuel in its tanks), the US government acknowledges that this “good luck ship” (a rough translation of its name) is an early taste of the estimated 1.5 million tons of tsunami debris expected to hit North American shores over the next two or three years. Similarly, the CRS report (titled Effects of Radiation from Fukushima Dai-ichi on the U.S. Marine Environment [PDF]) adopts an overall tone of “no worries here–its all under control,” but a closer reading reveals hints of “more to come.”

Indeed, the report feels as it were put through a political rinse cycle, limited both in the strength of its language and the scope of its investigation. This tension is evident right from the start–take, for example, these three paragraphs from the report’s executive summary:

Both ocean currents and atmospheric winds have the potential to transport radiation over and into marine waters under U.S. jurisdiction. It is unknown whether marine organisms that migrate through or near Japanese waters to locations where they might subsequently be harvested by U.S. fishermen (possibly some albacore tuna or salmon in the North Pacific) might have been exposed to radiation in or near Japanese waters, or might have consumed prey with accumulated radioactive contaminants.

High levels of radioactive iodine-131 (with a half-life of about 8 days), cesium-137 (with a half-life of about 30 years), and cesium-134 (with a half-life of about 2 years) were measured in seawater adjacent to the Fukushima Dai-ichi site after the March 2011 events. EPA rainfall monitors in California, Idaho, and Minnesota detected trace amounts of radioactive iodine, cesium, and tellurium consistent with the Japanese nuclear incident, at concentrations below any level of concern. It is uncertain how precipitation of radioactive elements from the atmosphere may have affected radiation levels in the marine environment.

Scientists have stated that radiation in the ocean very quickly becomes diluted and would not be a problem beyond the coast of Japan. The same is true of radiation carried by winds. Barring another unanticipated release, radioactive contaminants from Fukushima Dai-ichi should be sufficiently dispersed over time that they will not prove to be a serious health threat elsewhere, unless they bioaccumulate in migratory fish or find their way directly to another part of the world through food or other commercial products.

Winds and currents have “the potential” to transport radiation into US waters? Winds–quite measurably–already have, and computer models show that currents, over the next couple of years, most certainly will.

Are there concentrations of radioisotopes that are “below concern?” No reputable scientist would make such a statement. And if monitors in the continental United States detected radioactive iodine, cesium and tellurium in March 2011, then why did they stop the monitoring (or at least stop reporting it) by June?

The third paragraph, however, wins the double-take prize. Radiation would not be a problem beyond the coast? Fish caught hundreds of miles away would beg to differ. “Barring another unanticipated release. . . ?” Over the now almost 13 months since the Fukushima crisis began, there have been a series of releases into the air and into the ocean–some planned, some perhaps unanticipated at the time, but overall, the pattern is clear, radioactivity continues to enter the environment at unprecedented levels.

And radioactive contaminants “should be sufficiently dispersed over time, unless they bioaccumulate?” Unless? Bioaccumulation is not some crazy, unobserved hypothesis, it is a documented biological process. Bioaccumulation will happen–it will happen in migratory fish and it will happen as under-policed food and commercial products (not to mention that pesky debris) make their way around the globe.

Maybe that is supposed to be read by inquiring minds as the report’s “please ignore he man behind the curtain” moment–an intellectual out clause disguised as an authoritative analgesic–but there is no escaping the intent. Though filled with caveats and counterfactuals, the report is clearly meant to serve as a sop to those alarmed by the spreading ecological catastrophe posed by the ongoing Fukushima disaster.

The devil is in the details–the dangers are in the data

Beyond the wiggle words, perhaps the most damning indictment of the CRS marine radiation report can be found in the footnotes–or, more pointedly, in the dates of the footnotes. Though this report was released over a year after the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami triggered the Fukushima nightmare, the CRS bases the preponderance of its findings on information generated during the disaster’s first month. In fact, of the document’s 29 footnotes, only a handful date from after May 2011–one of those points to a CNN report (authoritative!), one to a status update on the Fukushima reactor structures, one confirms the value of Japanese seafood imports, three are items tracking the tsunami debris, and one directs readers to a government page on FDA radiation screening, the pertinent part of which was last updated on March 28 of last year.

Most crucially, the parts of the CRS paper that downplay the amounts of radiation measured by domestic US sensors all cite data collected within the first few weeks of the crisis. The point about radioisotopes being “below any level of concern” comes from an EPA news release dated March 22, 2011–eleven days after the earthquake, only six days after the last reported reactor explosion, and well before so many radioactive releases into the air and ocean. It is like taking reports of only minor flooding from two hours after Hurricane Katrina passed over New Orleans, and using them as the standard for levee repair and gulf disaster planning (perhaps not the best example, as many have critiqued levee repairs for their failure to incorporate all the lessons learned from Katrina).

It now being April of 2012, much more information is available, and clearly any report that expects to be called serious should have included at least some of it.

By October of last year, scientists were already doubling their estimates of the radiation pushed into the atmosphere by the Daiichi reactors, and in early November, as reported here, France’s Institute for Radiological Protection and Nuclear Safety issued a report showing the amount of cesium 137 released into the ocean was 30 times greater than what was stated by TEPCO in May. Shockingly, the Congressional Research Service does not reference this report.

Or take the early March 2012 revelation that seaweed samples collected from off the coast of southern California show levels of radioactive iodine 131 500 percent higher than those from anywhere else in the US or Canada. It should be noted that this is the result of airborne fallout–the samples were taken in mid-to-late-March 2011, much too soon for water-borne contamination to have reached that area–and so serves to confirm models that showed a plume of radioactive fallout with the greatest contact in central and southern California. (Again, this specific report was released a month before the CRS report, but the data it uses were collected over a year ago.)

Then there are the food samples taken around Japan over the course of the last year showing freshwater and sea fish–some caught over 200 kilometers from Fukushima–with radiation levels topping 100 becquerels per kilogram (one topping 600 Bq/kg).

And the beat goes on

This information, and much similar to it, was all available before the CRS released its document, but the report also operates in a risibly artificial universe that assumes the situation at Fukushima Daiichi has basically stabilized. As a sampling of pretty much any week’s news will tell you, it has not. Take, for example, this week:

About 12 tons of water contaminated with radioactive strontium are feared to have leaked from the Fukushima No. 1 plant into the Pacific Ocean, Tepco said Thursday.

The leak occurred when a pipe broke off from a joint while the water was being filtered for cesium, Tokyo Electric Power Co. said.

The system doesn’t remove strontium, and most of the water apparently entered the sea via a drainage route, Tepco added.

The water contained 16.7 becquerels of cesium per cu. centimeter and tests are under way to determine how much strontium was in it, Tepco said.

This is the second such leak in less than two weeks, and as Kazuhiko Kudo, a professor of nuclear engineering at Kyushu University who visited Fukushima Daiichi twice last year, noted:

There will be similar leaks until Tepco improves equipment. The site had plastic pipes to transfer radioactive water, which Tepco officials said are durable and for industrial use, but it’s not something normally used at nuclear plants. Tepco must replace it with metal equipment, such as steel.

(The plastic tubes–complete with the vinyl and duct tape patch–can be viewed here.)

And would that the good people at the Congressional Research Service could have waited to read a report that came out the same day as theirs:

Radioactive material from the Fukushima nuclear disaster has been found in tiny sea creatures and ocean water some 186 miles (300 kilometers) off the coast of Japan, revealing the extent of the release and the direction pollutants might take in a future environmental disaster.

In some places, the researchers from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) discovered cesium radiation hundreds to thousands of times higher than would be expected naturally, with ocean eddies and larger currents both guiding the “radioactive debris” and concentrating it.

Or would that the folks at CRS had looked to their fellow government agencies before they went off half-cocked. (The study above was done by researchers at Woods Hole and written up in the journal of the National Academy of Sciences.) In fact, it appears the CRS could have done that. In its report, CRS mentions that “Experts cite [Fukushima] as the largest recorded release of radiation to the ocean,” and the source for that point is a paper by Ken Buesseler–the same Ken Buesseler that was the oceanographer in charge of the WHOI study. Imagine what could have been if the Congressional Research Service had actually contacted the original researcher.

Can openers all around

Or perhaps it wouldn’t have mattered. For if there is one obvious takeaway from the CRS paper, beyond its limits of scope and authority, that seeks to absolve it of all other oversights–it is its unfailing confidence in government oversight.

Take a gander at the section under the bolded question “Are there implications for US seafood safety?”:

It does not appear that nuclear contamination of seafood will be a food safety problem for consumers in the United States. Among the main reasons are that:

- damage from the disaster limited seafood production in the affected areas,

- radioactive material would be diluted before reaching U.S. fishing grounds, and

- seafood imports from Japan are being examined before entry into the United States.

According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), because of damage from the earthquake and tsunami to infrastructure, few if any food products are being exported from the affected region. For example, according to the National Federation of Fisheries Cooperative Associations, the region’s fishing industry has stopped landing and selling fish. Furthermore, a fishing ban has been enforced within a 2-kilometer radius around the damaged nuclear facility.

So, the Food and Drug Administration is relying on the word of an industry group and a Japanese government-enforced ban that encompasses a two-kilometer radius–what link of that chain is supposed to be reassuring?

Last things first: two kilometers? Well, perhaps the CRS should hire a few proofreaders. A search of the source materials finds that the ban is supposed to be 20-kilometers. Indeed, the Japanese government quarantined the land for a 20-kilometer radius. The US suggested evacuation from a 50-mile (80-kilometer) radius. The CRS’s own report notes contaminated fish were collected 30 kilometers from Fukushima. So why is even 20 kilometers suddenly a radius to brag about?

As for a damaged industry not exporting, numerous reports show the Japanese government stepping in to remedy that “problem.” From domestic PR campaigns encouraging the consumption of foodstuffs from Fukushima prefecture, to the Japanese companies selling food from the region to other countries at deep discounts, to the Japanese government setting up internet clearing houses to help move tainted products, all signs point to a power structure that sees exporting possibly radioactive goods as essential to its survival.

The point on dilution, of course, not only ignores the way many large scale fishing operations work, it ignores airborne contamination and runs counter to the report’s own acknowledgment of bioaccumulation.

But maybe the shakiest assertion of all is that the US Food and Drug Administration will stop all contaminated imports at the water’s edge. While imports hardly represent the total picture when evaluating US seafood safety, taking this for the small slice of the problem it covers, it engenders raised eyebrows.

First there is the oft-referenced point from nuclear engineer Arnie Gundersen, who said last summer that State Department officials told him of a secret agreement between Japan and Secretary Hilary Clinton guaranteeing the continued importation of Japanese food. While independent confirmation of this pact is hard to come by, there is the plain fact that, beyond bans on milk, dairy products, fruits and vegetables from the Fukushima region issued in late March 2011, the US has proffered no other restrictions on Japanese food imports (and those few restrictions for Japanese food were lifted for US military commissaries in September).

And perhaps most damning, there was the statement from an FDA representative last April declaring that North Pacific seafood was so unlikely to be contaminated that “no sampling or monitoring of our fish is necessary.” The FDA said at the time that it would rely on the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to tell it when they should consider testing seafood, but a NOAA spokesperson said it was the FDA’s call.

Good. Glad that’s been sorted out.

The Congressional Research Service report seems to fall victim to a problem noted often here–they assume a can opener. As per the joke, the writers stipulate a functioning mechanism before explaining their solution. As many nuclear industry-watchers assume a functioning regulatory process (as opposed to a captured Nuclear Regulatory Commission, an industry-friendly Department of Energy, and industry-purchased members of Congress) when speaking of the hypothetical safety of nuclear power, the CRS here assumes an FDA interested first and foremost in protecting the general public, instead of an agency trying to strike some awkward “balance” between health, profit and politics. The can opener story is a joke; the effects of this real-life example are not.

Garbage in, garbage out

The Congressional Research Service, a part of the Library of Congress, is intended to function as the research and analysis wing of the US Congress. It is supposed to be objective, it is supposed to be accurate, and it is supposed to be authoritative. America needs the CRS to be all of those things because the agency’s words are expected to inform federal legislation. When the CRS shirks its responsibility, shapes its words to fit comfortably into the conventional wisdom, or shaves off the sharp corners to curry political favor, the impact is more than academic.

When the CRS limits its scope to avoid inconvenient truths, it bears false witness to the most important events of our time. When the CRS pretends other government agencies are doing their jobs–despite documentable evidence to the contrary–then they are not performing theirs. And when the CRS issues a report that ignores the data and the science so that a few industries might profit, it is America that loses.

The authors of this particular report might not be around when the bulk of the cancers and defects tied to the radiation from Fukushima Daiichi present in the general population, but this paper’s integrity today could influence those numbers tomorrow. Bad, biased, or bowdlerized advice could scuttle meaningful efforts to make consequential policy.

If the policy analysts that sign their names to reports like this don’t want their work used for scrap paper, then maybe they should take a lesson from the Ryou-Un Maru. Going where the winds and currents take you makes you at best a curiosity, and more likely a nuisance–just so much flotsam and jetsam getting in the way of actual business. Works of note come with moral rudders, anchored to best data available; without that, the report might as well just say “good luck.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.