NRC Chair Gregory Jaczko (photo: Gabrielle Pffaflin/TalkMediaNews)

For those that think nothing has changed in United States regulation since the Japanese earthquake and tsunami started the ongoing crisis at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear facility, think again. The pre-disaster mentality of “What could possibly go wrong?” has been replaced with reassurances that “Stuff like that hardly ever happens!”

At least that is the impression conveyed by the current chairman of the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Gregory Jaczko, in a pair of early October interviews. During two NRC-sponsored events, Jaczko fielded questions first from nuclear industry professionals and those considered friendly to the expansion of nuclear power, and then, in a separate session two days later, responded to representatives from public interest groups and other individuals generally seen as opposed to nuclear energy.

While the tone of the questions differed somewhat predictably in the two sessions, Chairman Jaczko’s attitude did not. Jaczko took several opportunities to praise the NRC staff and the processes and protocols used by the commission, repeating in both panels that the primary duty of his agency is ensuring the safety of nuclear facilities in the United States.

Beyond his broad assurances and patient, capable demeanor, however, many of the chairman’s assertions about both the NRC process and the progress being made toward his stated safety goals highlighted notable contradictions and troubling biases inherent in America’s nuclear regulatory regime.

To be fair, the pre-Fukushima outlook was not exactly “What could possibly go wrong?” In terms of the types of accidents and the repercussions of contamination, containment breaches, radioactive releases, meltdowns, melt-throughs, and a host of other undesirable situations, regulators and industry insiders alike were probably quite aware of what could go wrong. But as US nuclear proponents and profiteers strove to convey the impression of an informed industry, they also moved to downplay the threats to public safety and made sure to stress that, when it came to disaster scenarios, they had it covered.

If the disaster in Japan has proven one thing, though, it is that plant operators and nuclear regulators didn’t have it covered. Events (or combinations of events) that were either not foreseen or not acknowledged leave Japan scrambling to this day to understand and mitigate an ever-evolving catastrophe that has contaminated land and sea, and exposed yet-untallied thousands of Japanese to dangerous levels of radiation. “As we saw in Fukushima,” said Jaczko, “accidents still do happen in this industry. If we are thinking that they can’t, we are in a dangerous place.”

But for US nuclear regulators, there needn’t be any sense of urgency–or so believes the NRC chair. When asked why the agency doesn’t hold up plant relicensing until new standards that include lessons learned from the Japanese disaster are in place, Jaczko expressed confidence in the current system:

Bottom line is that changes get made at a plant. . . some changes will be made quickly, some may take years. It doesn’t matter where a plant is [in the process]–what is the licensing phase–but that changes get made. These are low frequency events, so we have some leeway.

It is a posture Jaczko took again and again in what totaled over two-and-a-half hours of Q&A–accidents are very, very rare. Given the history of nuclear power, especially the very recent history, his attitude is as surprising as it is disturbing. Beyond the depressingly obvious major disasters in nuclear’s short history, unusual events and external challenges now manifest almost weekly in America’s ageing nuclear infrastructure. The tornado that scrammed Browns Ferry, the flooding at Fort Calhoun, the earthquake that scrammed the reactors and moved storage casks at North Anna and posed problems for ten other facilities, and Hurricane Irene, which required a number of plants to take precautions and scrammed Calvert Cliffs when a transformer blew due to flying debris–all are external hazards that affected US facilities in 2011. Add to that two leaks and an electrical accident at Palisades, stuck valves at Diablo Canyon, and failures in the reactor head at oft-troubled Davis Besse, and the notion that dangerous events at nuclear facilities are few and far between doesn’t pass the laugh test.

That these “lesser” events have not resulted in any meltdowns or dirty explosions does nothing to minimize the potential harm of a more serious accident, as has been all too vividly demonstrated in Japan. The frequency or infrequency of “Level 7” disasters (the most severe event rating–so far given to both Chernobyl and Fukushima) cannot be used to paper-over inadequate safeguards when the repercussions of these catastrophes are so great and last for generations.

Storage concerns don’t concern

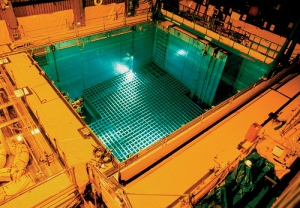

Chairman Jaczko’s seeming ease with passing current problems on to future generations was also in evidence as he discussed mid- and long-term storage of spent nuclear fuel. Though previously a proponent of an accelerated transfer of spent fuel from pools to dry casks, Jaczko now says, post-Fukushima, he has “no scientific evidence that one method is safer than the other.” The chairman made a point of noting that some dry casks at Virginia’s North Anna plant moved during the August earthquake, but said that it will be well over a year before we can evaluate what happened to wet and dry storage systems at Fukushima.

While it is true a full understanding will have to wait until after Daiichi is stabilized and decontaminated, it is already apparent that the spent fuel pools, which require a power source to actively circulate water and keep the stored fuel cool, posed dangers that in some ways rivaled the problems with the reactors. (So far, no Japanese plants have reported any problems with their dry casks.) So obvious was this shortcoming, that the NRC’s own staff review actually added a proposal to the Fukushima taskforce report, recommending that US plants take more fuel out of wet storage and move it to dry.

Jaczko’s newfound indifference is also odd in light of his own comments about dry casks as an alternative to a central nuclear waste repository. Asked in both sessions about the closing of Yucca Mountain (the proposed US site for spent nuclear fuel), the chairman buoyantly championed the possibility of using on-site dry casks for hundreds of years:

The commission is taking the appropriate action to address the storage of spent fuel. We have come to the conclusion that, over the short- and medium-term, safe storage is possible. We are taking a look at what is the finite limit on current [dry] storage. . . 200, 300, 400 years. Is there a time we have to move the fuel? . . . Nothing tells us we shouldn’t generate the [radioactive] material. We don’t see a safety concern out 100 years, or anything that says at 101 years, everything changes.

Chairman Jaczko then added that while the nuclear industry is generating waste that will require “long, long term storage or isolation,” it is not unprecedented to assume this problem can be taken care of by “future generations.”

It is good that Jaczko has such faith in the future, because his depiction of the present is not actually that impressive. While the NRC chief repeatedly touted their “process” for evaluating risks, problems, and proposals, he also painted a picture of a bureaucracy that has so far failed to fully act on the initiatives he has considered most important. Neither the fire-safety improvements Jaczko has championed since he came to the commission in 2005, nor the security enhancements required after 9/11/2001 have as yet been fully implemented.

Process is everything

Time and again, whether he was directly challenged by a question or simply asked for clarification, Gregory Jaczko referred to the NRC’s “process.” “We have a relicensing process,” “there is an existing process [for evaluating seismic risk],” there is a process for determining evacuation zones, there is a process for incorporating lessons learned from Fukushima, and there is a process for evaluating new reactor designs. Process, of course, is not a bad thing–in fact, it is good to have codified protocols for evaluating safety and compliance–but stating that there is a process is not the same thing as addressing the result. Too often, what might have sounded like a reasonable answer from the chairman was, in reality, a deflection. “The process knows all; trust in the process. I cannot say what will happen, and what I want to happen does not matter–there is a process.” (This, of course, is a dramatization, not a direct quote.) Form over functionary.

But Jaczko had barely started his second session when his reliance on process suffered an “unusual event,” as it were.

Asked about why the NRC seemed to be moving full-speed ahead with relicensing, rather than pausing to wait for Fukushima taskforce recommendations to be formalized, the agency chief first said, “There is an existing program, there are processes.” But within a breath, Jaczko then said, when it comes to lessons learned from Fukushima being some sort of prerequisite for final license approval, “We are going to look on a case-by-case basis.”

Is deciding whether to apply new requirements on a “case-by-case basis” actually a process? Many would say it pretty much defines the opposite.

The counter-intuitive also took a star turn when it came time to consider new externalities and pending environmental impact surveys. Shouldn’t the Fukushima taskforce findings be considered as part of a series of new environmental impact studies? Well. . . “It is clearly new information, but does it affect the environmental impact survey? Because they are very, very low likelihood events, it is not part of the environmental impact survey.” Jaczko here seems to be saying that unless you know in advance of the new study that the new information will alter the findings, you do not need to consider new information.

Shocked, shocked

With such confidence in the commission and its process, would it be safe to assume that Greg Jaczko is comfortable with the current state of nuclear safety in the United States? Perhaps surprisingly, and to his credit, the NRC head seems to say “no.”

As previously discussed, Jaczko expected faster action on fire safety and security upgrades. He also defended his going public with complaints about design problems with the AP1000 reactors proposed for Plant Vogtle:

We had been going back and forth with [AP1000 designer] Westinghouse for two years. I felt [a lack of] openness; felt if you aired the issues, they get addressed. Now, I feel it was. . . addressed. It ultimately forced these issues to get resolved.

Chairman Jaczko was also asked what tech issues keep him up at night:

Those components that are not replaceable, not easily inspectable. Those subjected to repeated exposure to high radiation, stresses that cause high degradation.

Jaczko said he felt the commission had a handle on what radiation does to the concrete in the containment vessel, but he was less sure about the effect of “shock,” which he defined as “repeated power trips” or scrams. Jaczko acknowledged that this increases stress on the containment vessels, and added, “Some places will not have 20 years [left] on pressure vessels. We get into an unknown piece of regulation on pressure vessel repair.”

That is a pretty stark revelation from a man so passionate about his agency’s ability to, uh, process new data, but it highlights another facet of Jaczko’s approach to regulation.

Noting that New Jersey’s Oyster Creek reactor was granted a renewed operating license for 20 years, but its operator later negotiated with the state to shut it down in 10 years, Jaczko said, “Extension is an authorization to operate, not a requirement to operate.” Relicensing, he said, might come with requirements for modifications or orders that they “monitor aging.”

Jaczko also said that states or facilities might decide it is not economically viable to keep a plant running for the full length of its license, “Like if you have a car and the clutch goes and you make a decision not to replace it.”

How to regulate, even without the Regulatory Commission

Yes, another deeply flawed automobile analogy, but note that Jaczko allows for, and maybe even expects, limits to a plant’s life that are not regulated by the NRC. And in detailing such, the chief regulator of the US nuclear industry shows where citizens might exercise leverage when his NRC fails.

First, there is that issue of economic viability. As previously discussed, the market has already rendered its verdict on nuclear power. In fact, it would be absolutely impossible to build or operate a nuclear plant without loan guarantees, tax breaks, and subsidies from the federal government. The new construction at Vogtle is projected to cost nearly $15 billion (and these plants always go way over budget), and the Obama administration has had to pledge $8.33 billion in loan guarantees to get the ball rolling. Without that federal backstop, there would be no licensing battle because there wouldn’t be the possibility of the reactors getting built.

In fact, in this time of questionable nuclear safety, deficit peacockery and phony Solyndra outrage, it is illustrative to note:

. . . in FY2010 alone, $2.82 billion went to natural gas and petroleum interests (through direct expenditures, tax expenditures, research and development funds, and loan guarantees), $2.49 billion to nuclear energy interests and $1.13 billion to solar interests.

Would any of the relicensing and new construction applications be before Jaczko’s NRC if the energy-sector playing field were leveled?

Second, at many points in the interview, federal regulator Jaczko referenced the power of the states. Early in the “pro” nuclear session, an anxious question expressed worry that states such as Vermont could play a role in the relicensing of reactors. While stating it was yet to be determined whether Vermont’s authority overlapped with the NRC, its chairman stated plainly that states do play a role. “States decide what kind of generating sources they use,” Jaczko said, “especially if the state has a public utility.”

When asked in the second panel if the NRC considers whether new rules or licensing delays will cause rate hikes for consumers, Jaczko said the final determination on rates was the purview of a state’s public utilities commission:

If the PUC denies charges, then they won’t get our approval to go forward–but if the PUC denies a rate change, they [the plant operators] still have to make the improvement required.

And when discussing how the NRC draws evacuation zones, Chairman Jaczko said that in the end, it was the responsibility of the state and local governments, acting on data from the utilities and advice from the NRC, to determine where, when and how to evacuate in case of a nuclear accident.

And, yes, that does sound again like some of the buck-passing that marked too much of these interviews, but it is also a roadmap for a possible detour around a recalcitrant or captured federal agency. If activists feel shut out of the regulatory process, they can attack the funding. If federal elected officials are not responsive (because they, too, have been captured by a deep-pocketed nuclear industry), concerned citizens can hit closer to home. As Jaczko says, states can choose their power sources, and states can define evacuation protocols that either better insure public safety or reveal continued operation of nuclear facilities to be untenable.

Such action would not be easy–state and local officials have their own interests and conflicts–but it might prove easier than a broad federal play. Recent successes by those seeking to close aging coal-fired generators show that action at the individual plant level is possible.

Open to openness

For anything to happen, of course, it is important that a dedicated and passionate citizenry organize around a tactic, or, if they prefer, a process. But it will also require a level of openness on the part of government. Sometimes that openness is offered, sometimes it is hard won, but without transparency, progress is hard to make and hard to measure.

Gregory Jaczko repeatedly stated that he is a big advocate of openness, and he offered these interviews in that spirit. These two events obviously didn’t go all the way in that direction–not even close–but the sessions had merit. Chairman Jaczko, despite all the problems detailed above, can still be admired for exhibiting something rather rare in today’s political climate, a regulator that actually believes in regulation. He, in fact, conveys a passion for it. That some of that regulation is based on flawed assumptions, and that much of it is weak or never enforced, cannot be ignored, but if the head of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission advocates for the regulatory process (even when hiding behind it), then there is at least a process to improve.

* * *

A version of this story was previously posted on Truthout.

You must be logged in to post a comment.