With Hurricane Sandy projected to make landfall hundreds of miles to the south and the predicted storm surge still over 24 hours away, New York City completely shuttered its mass transit system early Sunday evening. By 7 PM, all subway service was halted for only the second time in history. The fear, according to state authorities, is that heavy rainfall or the expected six-to-eleven-foot increase in tide levels would flood subway tunnels, stranding trains at various points across the 842 miles of track.

Fearing similar flooding, the Washington, DC, Metro is also expected to suspend service for all of Monday.

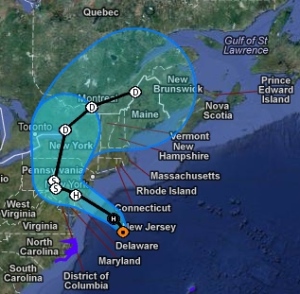

Twelve hours after NYC shut down its subways, at 7 AM Monday, with Hurricane Sandy lashing the Mid-Atlantic coast with heavy rain and 85 mph winds, at least a half-dozen commercial nuclear reactors lie in the storm’s projected path–and the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission has yet to issue any specific orders to the facilities it supposedly oversees. In fact, check out the NRC’s twitter feed or look at its website, and the only reference you will find to what has been dubbed “Frankenstorm” is the recently posted cancellation notice for a public hearing that was supposed to convene on Tuesday, October 30.

The subject of that meeting? The Fort Calhoun Nuclear Generating Station.

The Fort Calhoun plant sits on the Missouri River, on the eastern edge of Nebraska, near the town of Blair. Fort Calhoun’s single pressurized water reactor was shutdown for refueling in April of last year, but floods during the summer of 2011 encircled the facility and caused a series of dangerous incidents. A breach in water berms surrounded transformers and auxiliary containment buildings with two feet of water. Around that same time, a fire shut down power to Fort Calhoun’s spent fuel pools, stopping the circulation of cooling water for 90 minutes and triggering a “red event,” the second most severe classification. Outside of its reactor, the Nebraska facility is home to approximately 800,000 pounds of high-level radioactive waste. To this day, Fort Calhoun is offline and awaiting further evaluation by the NRC.

That a hearing on a flooded plant has been postponed because of the threat of flooding near NRC offices seems like the height of irony, but it pales next to the comparison of safety preparedness measures taken by New York’s Metropolitan Transit Authority for a subway and the federal government’s approach to a fleet of nuclear reactors.

That is not to say that the NRC is doing nothing. . . not exactly. Before the weekend, regulators let it be known that they were considering sending extra inspectors to some nuclear facilities in Sandy’s path. Additionally, regional officials stressed that plant operators were doing walk downs to secure any outside equipment that might become a sort of missile in the event of high winds. It is roughly the equivalent of telling homeowners to tie down their lawn furniture.

And it seems to be understood, at least at the nuclear plants in southern New Jersey, that reactors should be shutdown at least two hours before winds reach 74 mph.

To all that, the NRC made a point of assuring the public that reactor containment buildings could withstand hurricane-force winds, or any odd piece of “lawn furniture” that might be hurled at them.

That’s nice, but hardly the point.

Containment breech is always a concern, but it is not the main issue today. A bigger worry are SBOs–Station Black Outs–loss-of-power incidents that could impede a plant’s capacity to cool its reactors or spent fuel pools, or could interfere with operators’ ability to monitor everything that is going on inside those areas.

As reported last year, Hurricane Irene caused an emergency shutdown at Maryland’s Calvert Cliffs nuclear plant when aluminum siding torn off by high winds shorted out the main transformer and caused an explosion, damaging structures and equipment. Calvert Cliffs was one of the facilities that had chosen not to reduce output or shutdown in advance of Irene–especially alarming because just days before that storm, plant operators had reported trouble with its diesel backup generators.

Irene caused other problems, beyond loss of electricity to millions of consumers, public notification sirens in two emergency preparedness zones were disabled by the storm.

In sum, storm damage triggered a scram at a plant with faulty backup generators. If power had not been restored, backup would have failed, and the rising temperatures in the reactors and fuel pools would have necessitated an evacuation of the area–only evacuation would have been hampered because of widespread power outages and absent sirens.

The worst did not happen last year at Calvert Cliffs, but the damage sustained there was substantial, and the incident should serve as a cautionary tale. Shutting down a nuclear reactor doesn’t prevent every problem that could result from a severe storm, but it narrows the possibilities, reduces some dangers, and prevents the excessive wear and tear an emergency shutdown inflicts on an aging facility.

Calvert Cliffs is again in the line of fire–as are numerous other plants. Hurricane Sandy will likely bring high winds, heavy rain and the threat of flooding to nuclear facilities in Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey, New York and Connecticut. Given last year’s experiences–and given the high likelihood that climate change will bring more such events in years to come–it might have been expected that the NRC would have a more developed policy.

Instead, as with last year’s Atlantic hurricane, federal regulators have left the final decisions to private sector nuclear operators–operators that have a rather poor track record in evaluating threats to public safety when actions might affect their bottom line.

At the time of this writing, the rain in New York City is little more than a drizzle, winds are gusting far below hurricane strength, and high tide is still over ten hours away. Hurricane Sandy is over 300 miles to the south.

But Gotham is a relative ghost town. The subway turnstiles are locked; city busses are nowhere to be seen.

At the region’s nuclear facilities, however–at North Anna, Hope Creek, Salem and Oyster Creek, at Calvert Cliffs, Indian Point and Millstone–there is no such singular sense of better-safe-than-sorry mission.

In New York, it can be argued that the likes of Governor Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Michael Bloomberg have gone overboard, that they have made decisions based not just on safety, but on fears of political fallout and employee overtime. But in the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s northeast region, there is no chance of that kind of criticism–one might even say there is no one to criticize, because it would appear that there is no one in charge.

You must be logged in to post a comment.