Once there was an ocean liner; its builders said it was unsinkable. Nature had other ideas.

On Monday evening, as Hurricane Sandy was becoming Post-Tropical Cyclone Sandy, pushing record amounts of water on to Atlantic shores from the Carolinas to Connecticut, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission issued a statement. Oyster Creek, the nation’s oldest operating nuclear reactor, was under an Alert. . . and under a good deal of water.

An Alert is the second rung on the NRC’s four-point emergency classification scale. It indicates “events are in process or have occurred which involve an actual or potential substantial degradation in the level of safety of the plant.” (By way of reference, the fourth level–a General Emergency–indicates substantial core damage and a potential loss of containment.)

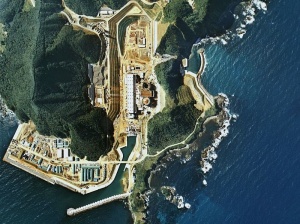

As reported earlier, Oyster Creek’s coolant intake structure was surrounded by floodwaters that arrived with Sandy. Oyster Creek’s 47-year-old design requires massive amounts of external water that must be actively pumped through the plant to keep it cool. Even when the reactor is offline, as was the case on Monday, water must circulate through the spent fuel pools to keep them from overheating, risking fire and airborne radioactive contamination.

With the reactor shut down, the facility is dependant on external power to keep water circulating. But even if the grid holds up, rising waters could trigger a troubling scenario:

The water level was more than six feet above normal. At seven feet, the plant would lose the ability to cool its spent fuel pool in the normal fashion, according to Neil Sheehan, a spokesman for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

The plant would probably have to switch to using fire hoses to pump in extra water to make up for evaporation, Mr. Sheehan said, because it could no longer pull water out of Barnegat Bay and circulate it through a heat exchanger, to cool the water in the pool.

If hoses desperately pouring water on endangered spent fuel pools remind you of Fukushima, it should. Oyster Creek is the same model of GE boiling water reactor that failed so catastrophically in Japan.

The NRC press release (PDF) made a point–echoed in most traditional media reports–of noting that Oyster Creek’s reactor was shut down, as if to indicate that this made the situation less urgent. While not having to scram a hot reactor is usually a plus, this fact does little to lessen the potential problem here. As nuclear engineer Arnie Gundersen told Democracy Now! before the Alert was declared:

[Oyster Creek is] in a refueling outage. That means that all the nuclear fuel is not in the nuclear reactor, but it’s over in the spent fuel pool. And in that condition, there’s no backup power for the spent fuel pools. So, if Oyster Creek were to lose its offsite power—and, frankly, that’s really likely—there would be no way cool that nuclear fuel that’s in the fuel pool until they get the power reestablished. Nuclear fuel pools don’t have to be cooled by diesels per the old Nuclear Regulatory Commission regulations.

A site blackout (SBO) or a loss of coolant issue at Oyster Creek puts all of the nuclear fuel and high-level radioactive waste at risk. The plant being offline does not change that, though it does, in this case, increase the risk of an SBO.

But in the statement from the NRC, there was also another point they wanted to underscore (or one could even say “brag on”): “As of 9 p.m. EDT Monday, no plants had to shut down as a result of the storm.”

If only regulators had held on to that release just one more minute. . . .

SCRIBA, NY – On October 29 at 9 p.m., Nine Mile Point Unit 1 experienced an automatic reactor shutdown.

The shutdown was caused by an electrical grid disturbance that caused the unit’s output breakers to open. When the unit’s electrical output breakers open, there is nowhere to “push” or transmit the power and the unit is appropriately designed to shut down under these conditions.

“Our preliminary investigation identified a lighting pole in the Scriba switchyard that had fallen onto an electrical component. This is believed to have caused the grid disturbance. We continue to evaluate conditions in the switchyard,” said Jill Lyon, company spokesperson.

Nine Mile Point Nuclear Station consists of two GE boiling water reactors, one of which would be the oldest operating in the US were it not for Oyster Creek. They are located just outside Oswego, NY, on the shores of Lake Ontario. Just one week ago, Unit 1–the older reactor–declared an “unusual event” as the result of a fire in an electrical panel. Then, on Monday, the reactor scrammed because of a grid disturbance, likely caused by a lighting pole knocked over by Sandy’s high winds.

An hour and forty-five minutes later, and 250 miles southeast, another of the nation’s ancient reactors also scrammed because of an interruption in offsite power. Indian Point, the very old and very contentious nuclear facility less than an hour’s drive north of New York City, shut down because of “external grid issues.” And Superstorm Sandy has given Metropolitan New York’s grid a lot of issues.

While neither of these shutdowns is considered catastrophic, they are not as trivial as the plant operators and federal regulators would have you believe. First, emergency shutdowns–scrams–are not stress-free events, even for the most robust of reactors. As discussed here before, it is akin to slamming the breaks on a speeding locomotive. These scrams cause wear and tear aging reactors can ill afford.

Second, scrams produce pressure that usually leads to the venting of some radioactive vapor. Operators and the NRC will tell you that these releases are well within “permissible” levels–what they can’t tell you is that “permissible” is the same as “safe.”

If these plants were offline, or running at reduced power, the scrams would not have been as hard on the reactors or the environment. Hitting the breaks at 25 mph is easier on a car than slamming them while going 65. But the NRC does not have a policy of ordering shutdowns or reductions in capacity in advance of a massive storm. In fact, the NRC has no blanket protocol for these situations, period. By Monday morning, regulators agreed to dispatch extra inspectors to nuclear plants in harm’s way (and they gave them sat phones, too!), but they left it to private nuclear utility operators to decide what would be done in advance to prepare for the predicted natural disaster.

Operators and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission spokes-folks like to remind all who will listen (or, at least, all who will transcribe) that nuclear reactors are the proverbial house of bricks–a hurricane might huff and puff, but the reinforced concrete that makes up a typical containment building will not blow in. But that’s not the issue, and the NRC, at least, should know it.

Loss of power (SBOs) and loss of coolant accidents (LOCAs) are what nuclear watchdogs were warning about in advance of Sandy, and they are exactly the problems that presented themselves in New York and New Jersey when the storm hit.

The engineers of the Titanic claimed that they had built the unsinkable ship, but human error, corners cut on construction, and a big chunk of ice cast such hubris asunder. Nuclear engineers, regulators and operators love to talk of four-inch thick walls and “defense-in-depth” backup systems, but the planet is literally littered with the fallout of their folly. Nuclear power systems are too complex and too dangerous for the best of times and the best laid plans. How are they supposed to survive the worst of times and no plans at all?

You must be logged in to post a comment.