Yes, it’s time for that metaphor again. If you grew up near a TV during the 1960s or ’70s, you probably remember the ever-burning Yule Log that took the place of programming for a large portion of Christmas Day. The fire burned, it seemed, perpetually, never appearing to consume the log, never dimming, and never, as best the kid who stared at the television could tell, ever repeating.

Now, if you have been watching this space about as intently as I once stared at that video hearth, perhaps you are thinking that this eternal flame is about to reveal itself as a stand-in for nuclear power. You know, the theoretically bottomless, seemingly self-sustaining, present yet distant, ethereal energy source that’s clean, safe and too cheap to meter. Behold: a source of warmth and light that lasts forever!

Yeah. . . you wish! Or, at least you’d wish if you were a part of the nuclear industry or one of its purchased proxies.

But wishing does not make it so. A quick look at the US commercial reactor fleet proves there is nothing perpetual or predictable about this supposedly dependable power source.

Both reactors at San Onofre have been offline for almost a year, after a radioactive leak revealed dangerously worn heat transfer tubes. Nebraska’s Fort Calhoun plant has been shutdown since April of 2011, initially because of flooding from the Missouri River, but now because of a long list of safety issues. And it has been 39 months since Florida’s Crystal River reactor has generated even a single kilowatt, thanks to a disastrously botched repair to its containment that has still not been put right.

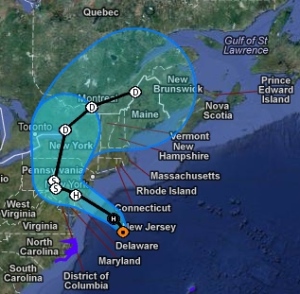

October’s Hurricane Sandy triggered scrams at two eastern nuclear plants, and induced an alert at New Jersey’s Oyster Creek reactor because flooding threatened spent fuel storage. Other damage discovered at Oyster Creek after the storm, kept the facility offline for five weeks more.

Another plant that scrammed during Sandy, New York’s Nine Mile Point, is offline again (for the third, or is it the fourth time since the superstorm?), this time because of a containment leak. (Yes, a containment leak!)

Other plants that have seen substantial, unplanned interruptions in power generation this year include Indian Point, Davis-Besse, Diablo Canyon, Hope Creek, Calvert Cliffs, Byron, St. Lucie, Pilgrim, Millstone, Susquehanna, Prairie Island, Palisades. . . honestly, the list can–and does–go on and on. . . and on. Atom-heads love to excuse the mammoth capital investments and decades-long lead times needed to get nuclear power plants online by saying, “yeah, but once up, they are like, 24/7/365. . . dude!”

Except, of course, as 2012–or any other year–proves, they are very, very far from anything like that. . . dude.

So, no, that forever-flame on the YuleTube is not a good metaphor for nuclear power. It is, however, a pretty good reminder of the still going, still growing problem of nuclear waste.

December saw the 70th anniversary of the first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction, and the 30th anniversary of the first Nuclear Waste Policy Act. If the 40-year difference in those anniversaries strikes you as a bit long, well, you don’t know the half of it. (In the coming weeks, I hope to say more about this.) At present, the United States nuclear power establishment is straining to cope with a mountain of high-level radioactive waste now exceeding 70,000 tons. And with each year, the country will add approximately 2,000 more tons to the pile.

And all of this waste, sitting in spent fuel pools and above-ground dry casks– supposedly temporary storage–at nuclear facilities across the US, will remain extremely toxic for generations. . . for thousands and thousands of generations.

There is still no viable plan to dispose of any of this waste, but the nation’s creaky reactor fleet continues to make it. And with each refueling, another load is shoehorned into overcrowded onsite storage, increasing the problem, and increasing the danger of spent fuel accidents, including, believe it or not, a type of fire that cannot be extinguished with water.

So, if you want to stare at a burning log and think about something, think about how that log is not so unlike a nuclear fuel assembly exposed to air for a day or two. . . or think of how, even if it is not actually burning, the high levels of radiation tossed out from those uranium “logs” will create heat and headaches for hundreds of thousands of yuletides to come.

Oh, and, if you are still staring at the Yule log on a cathode ray tube television, don’t sit too close. . . because, you know, radiation.

Merry Christmas.

You must be logged in to post a comment.